Women scientists and early pea research

At the turn of the 20th century, despite completing university degrees, women were still very much excluded from the scientific community and did not have the same access to college fellowships or studentships that enabled their male peers to kick-start their careers in science.

The new discipline of genetics offered a route into science for women, since it was not as dominated by established male hierarchies.

William Bateson was a supporter of equal rights and played a crucial role in creating the possibility of an academic career for would-be female scientists.

Female scientists at the John Innes ‘then’

After a short spell as Professor of Biology at Cambridge, Bateson left to become director of the new John Innes Institute at Merton, Surrey in 1910.

Bateson arranged that Studentships (£250 per year) and Minor Studentships (£50-£100 per year) would be offered to both men and women. This was particularly unusual for a scientific institute at this time.

Being prepared to work as volunteers or on low wages, these enthusiastic young women enabled Bateson to get the John Innes Institution off the ground and by the time the men left to fight in WW1, the women at the John Innes Institute outnumbered men 4:1. Our female staff also provided continuity and stability during this unsettled period.

Quickly an active and distinguished group of women scientists began to arise within Bateson’s team and they set about investigating the laws of inheritance in various organisms including pea.

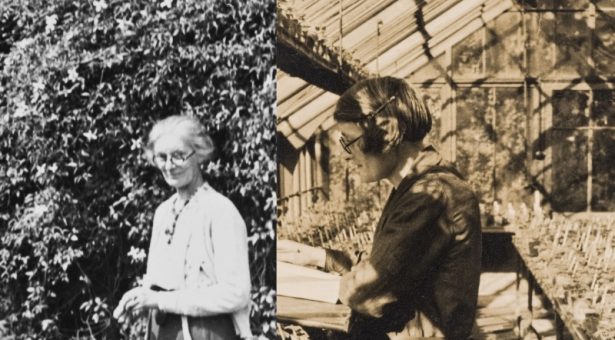

Caroline Pellew was awarded the first Minor Studentship at the John Innes Institute in 1910 and for 31 years she uninterruptedly carried out experiments and wrote numerous papers on pea. Caroline also acted as secretary and librarian of the John Innes Institute and was referred to as ‘Professor Bateson’s right-hand man’ by staff members.

Dorothea de Winton was another member of the group dubbed, ‘Bateson’s Ladies’ and assisted Bateson and Pellew in their study of pea. A passionate gardener, de Winton wrote a letter to Bateson in 1919 requesting a job and expressing her wish to eventually ‘go in more for the scientific side of it’. By 1929, she had proved her passion for genetics and was given the title of ‘geneticist’ and meticulously worked with pea for over 20 years.

The large numbers of female scientists at the John Innes Institute was unusual and was not met with full acceptance by some staff members. For example, C.D. Darlington joined the John Innes Institute in 1923, where he began his work in the segregated ‘ladies lab’. Archives reveal Darlington’s dislike of the female scientists, as well as a lack of appreciation for their work.

Darlington became the third Director of the John Innes Institute in 1939, at the start of WW2, when the Institute suffered a drop in income. He felt a change was needed and seized the opportunity to ‘move on’ the remaining ‘Bateson’s Ladies’.

A poem by Brenhilda Schafer about Darlington’s reorganisation of the John Innes Institute describes how the men were given the higher positions and more money, while the women were given the ‘toss’. Pellew and de Winton were the last to leave in 1941, marking the end of an era.

It can be argued that Darlington undervalued the work conducted by ‘Bateson’s Ladies’, suggesting that the John Innes Institute women primarily carried out breeding experiments designed by others. However, it is evident from their achievements that this was not the case; Bateson’s women can be considered innovators in their own right, with Pellew and de Winton leading pea research following Bateson’s death in 1926.

Between them, Pellew and de Winton published numerous papers on rogues, types and linkage in pea, thereby paving the way for the successful legacy of pea research at the John Innes Institute.

Female scientists at the John Innes ‘now’

Nowadays, gender equality has moved on significantly at the John Innes Centre.

By 2016, 49% of our staff members, 57% of our postgraduate researchers and 44% of our Researchers were female.

The John Innes Centre was also the first research institute in the UK to win an Athena Swan Gold Award, which recognises commitment to gender equality in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM).

Further reading

- Harvey, R. (1996). Bateson’s ladies. Typescript. John Innes Centre Archives

- Olby, R. (1989). Scientists and bureaucrats in the establishment of the John Innes Horticultural Institution under William Bateson. Annals of Science, 46, 497–510. DOI: 10.1080/00033798900200361

- Richmond, M. L. (2001). Women in the early history of genetics: William Bateson and the Newnham College Mendelians, 1900-1910. Isis, 55-90. DOI: 10.1086/385040

- Richmond, M. L. (2007). Opportunities for women in early genetics. Nature Reviews Genetics, 8(11), 897-902. DOI: 10.1038/nrg2200