An exciting new landscape of protein-related discovery unfolds

An investigation into cellular components in bacteria has unexpectedly uncovered a feature with relevance across many life forms, paving the way for diverse research, biotechnical and medical applications.

Researchers in the group of Professor Tung Le at the John Innes Centre, in collaboration with Dr Antoine Hocher at Cambridge University, set out to probe the key protein ParB which helps bacteria segregate replicated or “sister” chromosomes, a vital stage in cell division, and therefore vital to survival.

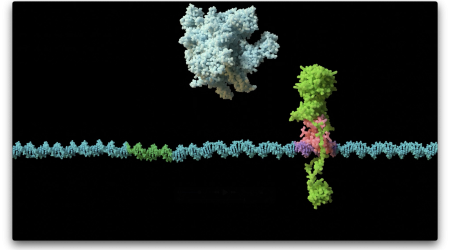

ParB protein acts like a molecular “clamp” that entraps and slides along DNA; this way multiple ParB proteins accumulate on DNA to serve as a handle to help move replicated sister chromosomes apart to each new “daughter” cell.

This field was revolutionised six years ago with the discovery that ParB binds and breaks down a small-molecule nucleotide called CTP to “switch” between an open and a closed clamp form, identifying ParB as the first known CTP-dependent molecular switch.

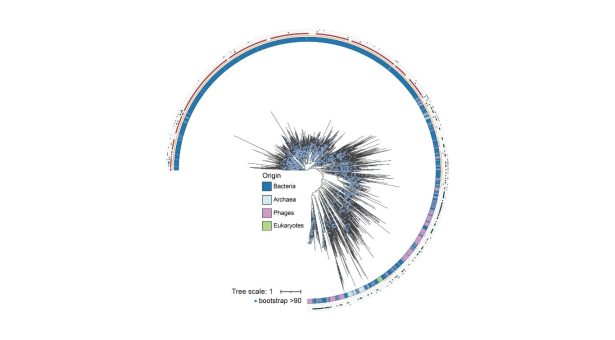

This more recent John Innes Centre-led collaboration built on this discovery with a large-scale survey that reveals that the structural feature that enables CTP binding, known as the ParB-CTPase fold, extends much further than previously thought.

Combining bioinformatics and biochemistry, they show the fold is a widespread feature across many forms of life in addition to bacteria, including archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses.

The research, which appears in the peer-reviewed journal PNAS, additionally shows that the fold is versatile – not only binding to CTP, but also to other ubiquitous nucleotides including ATP and GTP, including the first examples of GTP-binding ParB-like proteins.

This versatility suggests previously unrecognised biological functions and might open a wealth of discovery opportunities in the field.

Co-first and co-corresponding author, Dr Jovana Kaljević, at the John Innes Centre, said: “It was so exciting to see how a single protein fold, long studied in bacteria, connects a vast range of proteins found across all domains of life. This shows that evolution has repeatedly repurposed the same molecular architecture for entirely divergent functions. This finding sets the stage for a new field exploring the evolution, mechanism, and functions of ParB-like proteins across domains of life.”

Dr Kirill Sukhoverkov, a co-first author, added : “The next step for the researchers is to expand comparative, biochemical, and structural analyses to define sequence and structural features that predict whether a given Par–B–CTPase fold prefers CTP, ATP, GTP, or other small molecules”.

More broadly the research could also lead to insights into genetic regulation, biotechnology applications, and new strategies for tackling antimicrobial resistance, one of the major threats to human health in the 21st century.

Versatile NTP recognition and domain fusions expand the functional repertoire of the ParB-CTPase fold beyond chromosome segregation, appears in PNAS.

Image Credit: Dr Jovana Kaljević & Dr Antoine Hocher

Caption –

The circular tree shows how thousands of ParB-like proteins are distributed and have evolved across bacteria, archaea, phages, and eukaryotes. The coloured rings highlight the origin of each protein and whether it retains key features, such as the canonical ParB structure or the ParA-binding sequence. Long branches reveal fast-evolving, highly diverged versions of the fold, offering a glimpse into how this ancient protein family has diversified across life.