Why do tulips break?

With the John Innes tulip collection growing, attention turns to the mystery of tulip breakage.

Sarah Wilmot returns with Part 2 of our history of tulip research at the John Innes Centre. Catch up with Part 1 – ‘Tulip research springs into life’ here.

“With the collection expanding, Hall pressed John Innes’ mycologist Dorothy Cayley into service to try to settle the question once and for all as to whether a virus was the cause of ‘breaking’ in tulips.

Breaking is where the tulip, instead of being of one or more uniform colours, becomes striped or splashed. In the past florists had often prized these broken forms and tried to induce it artificially, but the Dutch growers raising bulbs for the 20th century market wanted their ‘breeder’ tulips free of breaks.

A pathological change in the bulb had long been suspected, but experiments had failed to find a fungus or bacterium in the broken bulbs.

At the start of the 20th century ‘virus’ diseases of plants had not been recognised and were not looked for (viruses are too small to see with a light microscope). The term ‘virus’ began to be applied to certain infections that cause a mosaic or variegation in the foliage of a plant- most famously the tobacco mosaic virus which was first ‘crystallized’ (isolated) in 1935.

As knowledge began to accumulate on virus diseases in other plants, for example the idea that these diseases are usually transmitted by insects feeding on the plant, it began to be seen that breaking in tulips was a similar phenomenon. In Bateson’s time E J Collins had tried to prove it by experiments but had been unsuccessful in that some of his ‘control’ bulbs had also broken. It was down to Dorothy Cayley to finish the job.

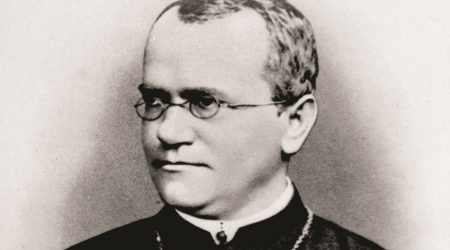

Cayley had been at the John Innes since it first opened in 1910 and by 1927 when her work on tulips began, she was a very experienced researcher of fungal diseases, quickly obtaining the experimental proof Hall was looking for that ‘breaking’ was caused by an ‘infectious agent’ or virus.

Having grafted halves of known broken bulbs onto bulbs of a stock of ‘Bartigon’ which (as far as controls could tell) were free from broken forms, Cayley found 26% of the in-contact bulbs broke in the first year. She also got bulbs to break by inserting a plug of the pounded-up tissue from a broken bulb, but the introduction of a filtered juice from a broken bulb did not cause breaking.

She published her results in the ‘Annals of Applied Biology’ in November 1928, and in a follow-up paper in 1932, and has ever since been credited as the scientist who solved the puzzle of ‘breaking’ in tulips.

By the end of the 1930s, Hall was able to put together the fruits of by-now almost 20-years of research on tulips at the John Innes.

In ‘The Genus Tulipa’ (published in 1939) Hall presented the findings of chromosome studies that were begun by Frank Newton and added to by members of the expanding cytological department under Darlington, including Len Lacour and Margaret Upcott.

Hall also reported on tulip breeding experiments initiated by Dr J. Philp, and on biochemical experiments on the nature of the anthocyanin pigments by Dr J. R. Price. From the chromosome studies came the recognition of a number of polyploid species (species with multiple sets of chromosomes) that had previously been confused with their corresponding diploids (two sets of chromosomes). Frank Newton had established that in Tulipa there are triploids, tetraploids and one pentaploid. The John Innes staff had since studied the chromosomes of 80 species of tulip in cultivation. Combined with other data, these studies confirmed Tulipa as mainly an Asiatic genus, having its focus in the hilly regions of Asia Minor, the southern Caucasus, Persia, Turkistan and Bukhara.

1939 was of course significant for other reasons and one commentator remarked that Hall’s book would surely have created much more of an appreciative splash in the horticultural world had it not been overshadowed by the outbreak of war.

Regardless, Hall was awarded the Veitch Medal of Honour in 1939 in recognition of his contributions to horticulture and the RHS made him a Vice President. 1939 was also the year that Hall finally decided to retire from John Innes (age 75) – perhaps the tulips were responsible for him staying on so long?”

The third and final part to this story; ‘Studying the tulip chromosome and inspiring the future’ is available here.