Placing Mendel back among the Mendelians

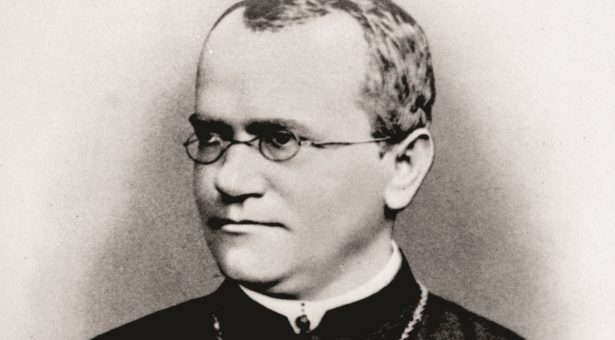

Two new studies have mounted a robust defence of Gregor Mendel against historic criticism that questions his place as “Father of Genetics.”

The research is the latest in a series of events and publications to mark Mendel’s bicentenary, a year-long celebration which ends in July.

A friar based at a monastery in Brno, Moravia, Mendel used his experiments crossing pea plants to establish simple numerical relationships about how characteristics are passed down through the generations and in so doing laid the foundation for the science of genetics.

But since his death in 1884 some people – including esteemed scientists – have doubted Mendel’s findings and even questioned whether his work fits into the field named after him – Mendelian genetics.

In recent years leading up to Mendel’s bicentennial, John Innes Centre researcher Dr Noel Ellis and his collaborator Dr Peter van Dijk of Netherland’s based crop breeding tech company KeyGene, have embarked on an academic quest to scrutinize historic and some contemporary criticisms of Mendel.

It’s a mission which has taken them across Europe to events and conferences and for van Dijk, it brought the award of the Mendel Memorial Medal, earlier this year. Together they have trawled newly available online sources to gain a clearer impression of Mendel as man and scientist. Their most recent defence of Mendel appears as an article in Hereditas and examines Mendel’s terminology; his use of terms such as dominant, recessive, character, element and factor and his use of symbols to describe his plants.

Some have claimed that Mendel had no notion of a genotype – the genetic constitution of organisms – that he thought more about the outward traits. This is strongly rebutted by Ellis and van Dijk.

“Critics have said that he did not have a sense of genetics that he concentrated on the phenotype rather than the genotype. However, in our paper we show that Mendel’s use of symbols was not describing the thing as it was but how it would look if he did a cross – so that is clearly closely related to a genotype,” says Ellis.

“Genotyping as Mendel thought about it is about predicting how an organism is going to behave – it’s a mental construct,” he continues. “And the phenotype is the actual thing. So, a lot of what people talk about as genotyping is really phenotyping.”

Another study in the journal Genetics defends Mendel against critics – including the historian Robert Olby who in a provocatively named article “Mendel no Mendelian?” said that Mendel’s seminal 1866 paper was not primarily about inheritance of traits but how new species may emerge through hybridization of existing species.

In this study Ellis and van Dijk – using new sources – argue that while Mendel’s initial focus was on plant breeding, he became curious about segregation patterns of seed traits which led to an investigation into the inheritance of other traits.

“Chromosomes and meiosis were not yet known in Mendel’s lifetime, but he wrote nothing that was in conflict with later Mendelism, as Olby suggested,” said van Dijk.

These papers can be placed alongside earlier research which defended Mendel’s use of statistics against charge made by mathematician R.A Fisher that Mendel’s findings were “too good to be true.” In fact, a revisiting of the paper shows his findings to be “exemplary.”

Another misconception that Mendel was a reclusive working chiefly behind monastic walls was rebutted by evidence available online about his international travels to Paris and London, to Rome and Naples and to Hamburg and Kiel.

But aside from intellectual curiosity, why should contemporary researchers feel a sense of mission in defending Mendel against his critics?

Ellis explains: “Any remarkable scientist is open to challenge, and they should be challenged, it is perfectly legitimate. I just got annoyed because I thought the challenges were unjustified and these papers of ours have shown Mendel to be correct given the constraints he acted within.”

Having trailed Mendel for many years gathering information from his scientific and cultural activity, what picture emerges?

“He was clearly very insightful, a clear thinker and particularly good at explaining. If you read the 1866 paper it is astonishingly clear and logically laid out. If you read Darwin’s Origin of Species, it is by comparison harder to follow. Mendel is much more of what we think as a scientist rather than a natural historian.”

Mendel is a matter of current as well as historical importance, adds Ellis: “There is something of a campaign to remove the teaching of Mendelian genetics from schools because it is seen as too deterministic.

“There is also a lot of concern, not unreasonably, about genetics in relation to race and eugenics, and one of the ways of arguing against such things is to criticize Mendel – which is a mistake. It is making a false connection.”

Mendel’s bicentenary year has led to numerous publications. It seems certain that part of his scientific legacy is to inspire spirited debate. But for his admirers Mendel’s bicentenary has been a chance to revisit his findings. For them, his scientific inheritance is intact.

Mendel’s terminology and notation reveal his understanding of genetics appears in Hereditas.

Gregor Mendel and the theory of species multiplication appears in Genetics

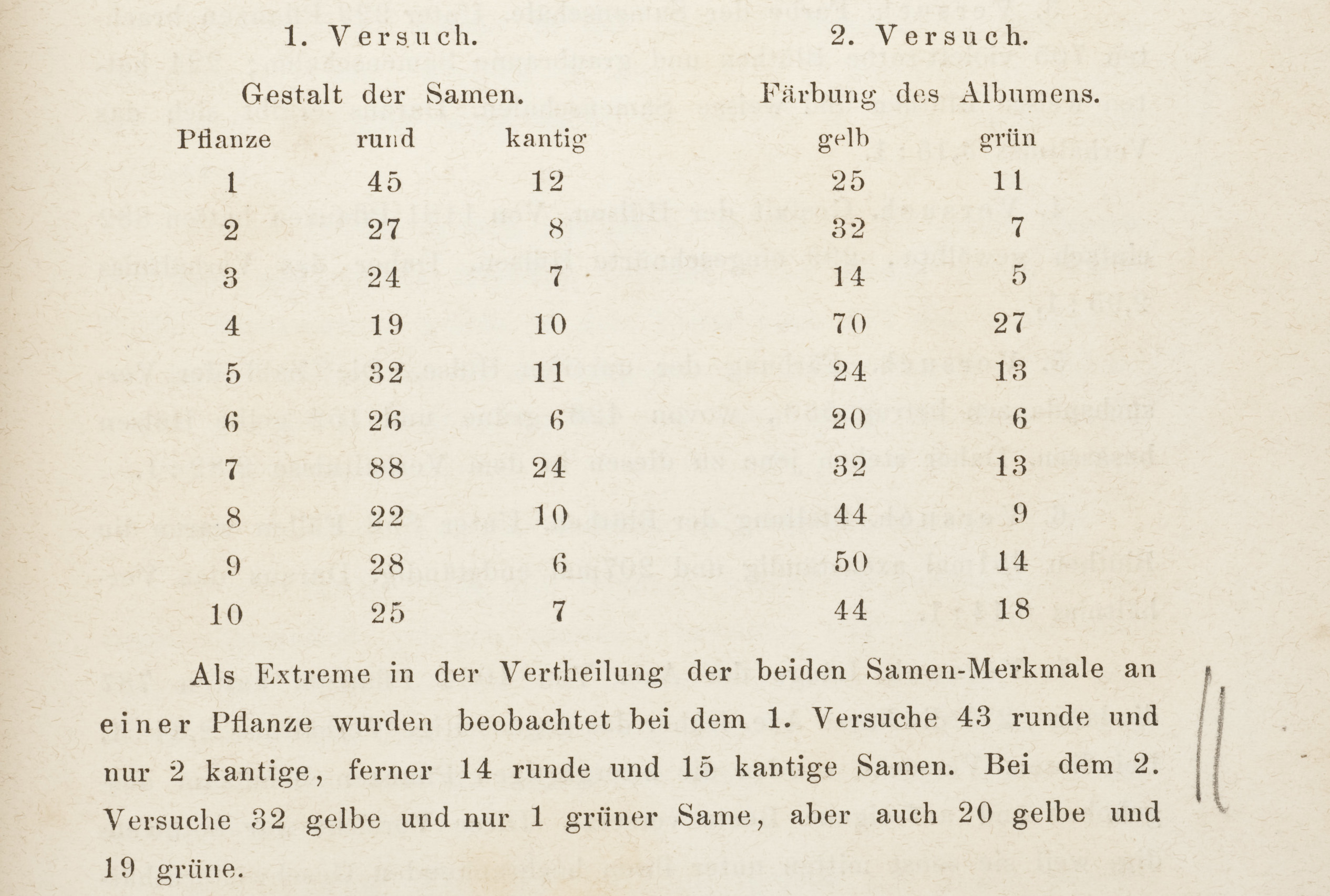

Caption – Noel Ellis explains: “The extract shows a place in Mendel’s 1866 paper where he is discussing the variability of the segregation ratio among the offspring of different individuals. Below the table Mendel gives four examples of segregation ratios very far from expectation (nearly 1:1 and 1:0 rather than 3:1). William Bateson (first director of the John Innes Centre) has highlighted these examples with two lines in the margin. He has not highlighted the examples that agree well with expectation.

That Mendel presented these data shows clearly that he wanted to make clear that the 3:1 ratio was an average and that any particular example could be quite different. It shows that he was not trying to restrict the data he presented only to those examples that were a good fit to his hypothesis.

Image credit – The John Innes Archives courtesy of the John Innes Foundation