Disability at work: looking back through John Innes history

The annual observance of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities took place on 3 December, with an aim to promote an understanding of disability issues and mobilize support for the dignity, rights and well-being of those with a disability. As such, we take a look back at John Innes Centre history, delving into the archives to discover the stories of two figures who worked at the institute with disabilities and differences.

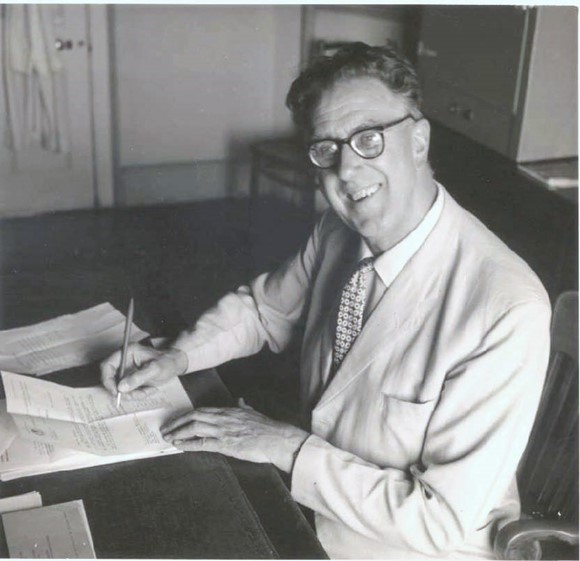

William J C Lawrence

William J C Lawrence (1899-1985) is most remembered as the co-inventor of the John Innes compost, and began his working life at the John Innes Horticultural Institute (JIHI) as an unpaid garden boy. Less well known is the fact that his parents, urged by their doctor, found him this position to ‘save his eyesight’.

““The boy may go blind unless he gets a job out of doors”- the family doctor was speaking to my parents and his words half true, half false, decided my career, indeed my life!” [1]

Lawrence was almost certainly suffering from worsening myopia, a condition better known as short-sightedness, which in severe cases can lead to disabling or even complete sight loss, especially in the era before modern medical interventions. Myopia typically develops in children between the ages of 8 and 15.

In his memoir Catch the Tide, Lawrence recalls getting his first pair of spectacles at age 7 and being able to see the school blackboard for the first time.

In the early 20th century myopia was associated with urban living conditions, close and indoor work. The treatment, particularly for children, was to spend more time outdoors, hence his family finding him a job working outdoors at the JIHI.

Lawrence had been head-boy in his last year at school and put forward for a prized scholarship, but a bad case of measles meant he had to spend six weeks at home, and he subsequently failed his scholarship exam. This prevented him from continuing his education. His worsening health also lost him a job that his parents procured him at the ‘National Amalgamated Assurance Company’.

The family were in despair until someone suggested they try at Merton, a ten-minute walk from the family home in Wimbledon. William Bateson, the then Director, was at first reluctant to take him on and it was only after his parents visited him in person, explained his medical condition and offered his services free of charge that he was accepted.

This is how Lawrence, at 14, started work as an unpaid garden boy at Merton, the farm and gardens belonging to the John Innes Horticultural Institute, on the outskirts of London.

Lawrence thrived at Merton. He went on to train and work at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, after serving in the Royal Engineers. He re-joined the John Innes Institute as a paid member of the scientific staff in 1924, starting research on the inheritance of flower colours in Dahlia and going on to contribute important work in the field of plant genetics and cytology.

He was Curator to the Institute also was acting Director for a time. In the 1930s he worked alongside John Newell to create the famous John Innes Seed and Potting Composts. He became Head of the Garden Research Department, a position which was specially created for him after the success of his work on compost. He published important works on a variety of horticultural topics and received an OBE in 1955.

[1] WJCL in his unpublished memoir Catch the Tide (c 1968), John Innes Centre Archives.

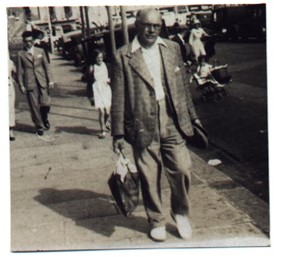

Herbert Osterstock

Herbert Charles Osterstock (1876-1942) was an artist, illustrator, and photographer. He designed apparatus for various experiments as well as being the unofficial resident camera and watch repairer.

He began working with scientists at the John Innes in about 1912 at the age of 26, becoming permanent full-time artist and photographer for the institute from 1925. He is most known for his beautiful painted illustrations of tulips for Sir A Daniel Hall’s book The Genus Tulipa (1940). Scientific recording at this time required skilled illustration and the hand colouring of photographs.

Although relatively young when he joined, he was already an established illustrator and cartoonist for the Whitehall Gazette and St James Review under the name Sphinx, for which he produced portraits and cartoons of the notable heads of state and royalty of Europe. The Royal Collection has a full-length portrait painting of Prince Albert (later George VI) by Osterstock painted in c. 1920s, and he seems to have continued this work in tandem with his work with the JII until at least 1925.

Not much is known about Osterstock’s background: the National Portrait Gallery entry under his photographic portrait of William Bateson notes that he was born in Camberwell to a German family who settled in England in the 1820s. Recent research by his grandson, Paul Gillard has tentatively extended his family tree back to Johann Fredrich Osterstock, a fur skin dresser born in 1784, Wurttemberg.

According to Gillard, Herbert contracted meningitis sometime in 1880, which left him completely deaf. He was noted as being deaf in the 1881 census. Becoming deaf at such an early age meant that his speech was also curtailed. Family members remember him attending a school for deaf children described as ‘Avant-guard.’ He was still a ‘scholar’ in the 1891 census when aged about 15.

In Osterstock’s time, the teaching of sign language was actively discouraged in favour of ‘oralism’: a method that focused on learning speech articulation and lipreading, to conform to the expectations of hearing society. In various accounts from his JIHI colleagues, he is noted as being able to lip read, as using ‘a form of sign language’ and as ‘able to talk after a fashion.’

Gillard was unable to find out where he attended school or how he received his artistic training. However, he noted that Osterstock’s father worked as a printer/stationer in London for the Henry Good & Son company and by 1901, Osterstock was employed as a ‘lithograph artist’, possibly at the printer’s company where his father worked.

Another family rumour has it that he was under the tutelage of a well-known artist somewhere near Duke Street in central London, where he met his future wife Minnie, who worked as a barmaid at the nearby Red Lion. Minnie’s father was a Book Gilder. They were married by the Chaplain for the Deaf and Dumb at St Thomas’ in 1911.

Osterstock is remembered for his amazing abilities as an artist and as an inventor of mechanical devices. In an interview for the JIHI in 1981, B J Harrison, who worked with Osterstock in the 1930s, recalls how “he could paint things so accurately and in such detail that they made excellent records… before we had coloured photography ….and he could, sort of make anything…”[1]

This included making his own cameras and rigging up devices to make his own, and his colleagues work easier.

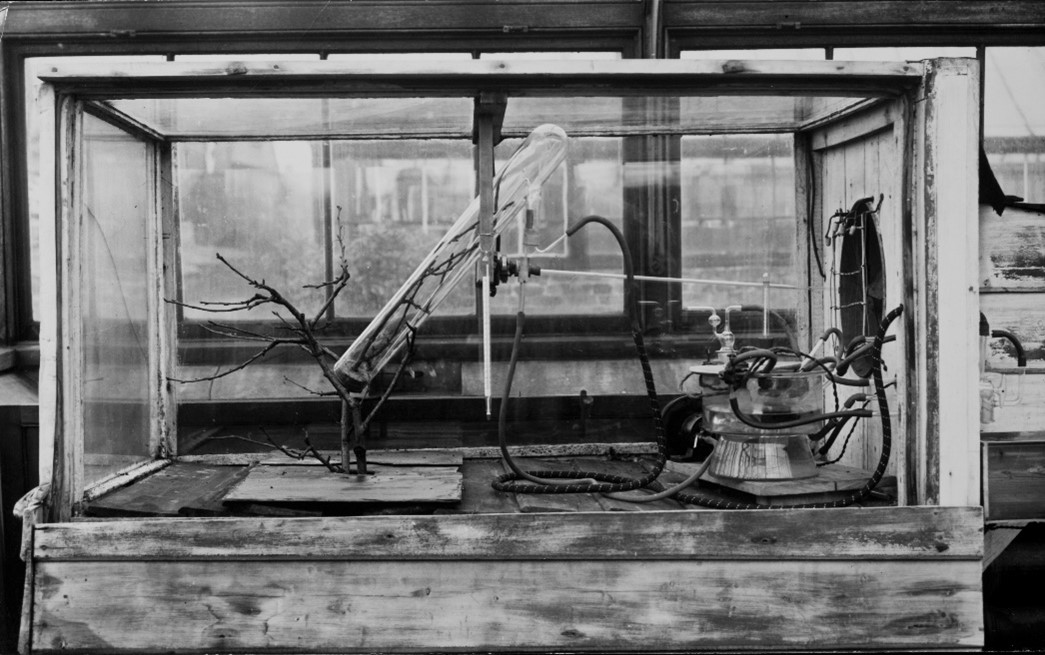

There is a photograph in the John Innes Centre archives of a ‘constant temperature cabinet’ designed by Osterstock for Dan Lewis which used mustard gas to produce mutant cherry seedlings to use in genetic research.

Harrison remembers him rigging up various devices to make photography easier including “little contraptions that fitted on top of microscopes, taking photographs” and making an air brush device out of an oil drum, “he connected it to a rubber tube and he’d do all his backgrounds in….I hadn’t ever even heard of it in those days….Anything like that, he’d just make it out of all sorts of bits and pieces.” [2]

William Lawrence remarks on how he made all sorts of devices and apparatus for cameras and microscopes “from odd scraps of material with great ingenuity” and how he frequented the Farringdon Market on Wednesday afternoons to look for “oddments” to use in his constructions[3].

Lawrence also notes that he was the “unofficial watch repairer to the Institution”, corroborated by Charles Henderson who notes, briefly, in his diary “Got my watch back from Osterstock[4].”

William Lawrence wrote the obituary for Osterstock after his death in May 1942. In the Journal of the John Innes Association, Lawrence lamented the loss to the Institution of “one of its outstanding personalities” and lauded his multiple talents, “Osterstock was as clever in inventing and making all sorts of mechanical devices as he was with the brush.”

[1]B J Harrison, ibid.

[2]B J Harrison, ibid.

[3]The Journal of the John Innes Association, Jan,1943, pp16-17.

[4]Diary of Charles Henderson, (copy), p. 105, John Innes Centre Archives.

For more info and other resources about the histories of people who were deaf or experienced hearing loss, check out: Deaf lives – The National Archives