The John Innes Centre and the compost that bears our name

As Britain’s gardeners head out into their gardens and on to their allotments, soil quality and compost will be forefront of many minds.

Just as flowers and vegetable beds are exploding into life, so too does our mailbox – bulging with enquiries about the compost that bears our name.

Sadly, we are unable to help, because while our scientists developed the recipe for what came to be called John Innes compost in the 1930s, we have never manufactured, supplied or sold compost for public use and have never benefited financially or otherwise from the production of John Innes Compost.

This is the story of how our name came to adorn those polythene bags.

In the 1930s two research workers at the ‘John Innes Horticultural Institution’, William Lawrence and John Newell, set out to overcome the problems associated with traditional composts and to formulate composts that would give consistently good and reliable results.

The pair had been inspired by heavy losses of the Chinese primrose (Primula sinensis) seedlings in the 1933-34 season. At the time Dorothea de Winton and JBS Haldane were trying to understand the genetics of the plant, and their experiments relied on healthy germination of seedlings.

While less well-known than Haldane, de Winton discovered over 20 mutants and was able to demonstrate double that number over a two-decade career working on P. sinensis. Her studies formed the basis of linkage studies and were appreciated each year by large numbers of genetics students. To honour de Winton’s contribution to genetics, we named our new Field Experimentation facility after her in 2019.

After nearly six years of experiments and hundreds of trials, Lawrence and Newell perfected methods of soil sterilisation, and established the physical properties and nutrition necessary in composts, to achieve optimum rates of plant growth, arriving at two standardised ‘John Innes’ composts, publishing, but not patenting them in 1938.

They also introduced methods of heat sterilising the soil with steam, showing that this eliminated pests and diseases, but did not cause any problems for plant growth. The methods required to make the composts were published in 1939 in a pamphlet entitled ‘Seed and Potting Composts’.

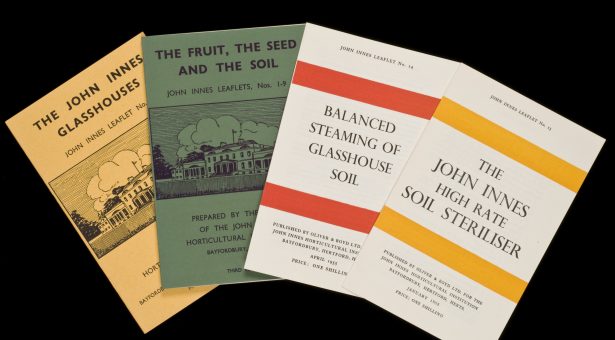

As part of the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign during World War 2, the compost recipe and heat sterilisation process were both released to the public to help feed a rationed population. To further the war effort, John Innes staff also published a series of leaflets and gave radio broadcasts to publicise their new composts and other improved methods for raising garden crops.

As the old saying goes, the rest is history. We made the formula available and the horticultural retail trade adopted the methods and sold their own versions of our original recipes as ‘John Innes Compost’. Their success made ‘John Innes’ a household name.