The Scopes Monkey Trial; what we can learn about the communication of science

In 1925, an American school teacher was put on trial for teaching evolution.

This was global news and an important moment in the ever-changing relationship between science and religion.

The 2020 Innes Lecture told the story of the Scopes Monkey Trial and highlighted the key themes in the public reactions. We asked Professor Joe Caine, why did so many people hate evolution and what can we learn from the trial today?

“We’re in 1925. In Tennessee USA, which is on the western side of the Appalachian mountains. It’s rural. It’s also strongly evangelical Christian (protestant).

In this context, the local legislature passes a law which effectively bans the teaching of evolution in state schools. The focus of attention is on the teaching of human evolution and the impact that might have on moral education for children.

Some people thought the law was an intrusion of religious ideas into civil society so they challenged it. To do so, they find a teacher/volunteer (John Scopes) who is willing to say they taught evolution, and then the local authorities charge him with breaking the law.

The Scopes Trial is the court case about this alleged offense. The defence argued the law was unconstitutional. The prosecution argued Scopes broke the law.

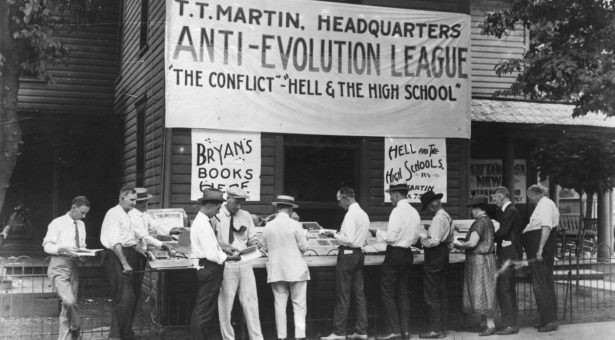

At the start, it’s choreographed on all sides and was more than a courtroom event. Instead, it was a circus come to town. The trial occurred in the quiet “silly season” for the press and built into media frenzy. Celebrities flocked to the event for the light of publicity. Everyday folk headed to the trial for entertainment in the summer holiday. It was a great commercial success for the town, too.

The trail runs for a week and a half during the hot summer of 1925, with barristers for these two sides fighting their case. Most of it was dry legal procedure, but there were some moments of great oratory, and a few spirited clashes made headlines.

The judge chose to interpret the case narrowly (focusing on whether the law was broken), which the jury found Scopes guilty of.

The defence always expected to lose, so their strategy was to pack the trial with material they wanted to use on appeal.

In an unexpected turn, the judge made a procedural mistake in Scopes punishment (he was fined more than the law instructed). That allowed the appeals court to put aside the guilty verdict and they asked for the state to prosecute Scopes again.

However, after the fiasco of the first trial, no one had the appetite to repeat it so the case stopped there.

That was a frustrating result, because it left everyone in limbo: Scopes was no longer guilty; there no longer was a case to appeal. The anti-evolution law was effective in Tennessee until repealed in 1968.

At the time there wasn’t much impact on science, or scientific communication and academic scientists working on evolution kept to their ivory towers.

Some historians think the teaching of evolution disappeared from state schools across America as a result of the trial’s “chilling effect”, but recent work shows evolution was only minimally present in the curriculum before the trial – most biology in most schools emphasised practical things, such as nutrition, health, ecology, agriculture, and disease.

A few historians have studied what happened in the public understanding of evolution in practical sciences, such as agriculture and horticulture.

The results seem to show that few people had problems with ideas like selection or evolutionary relationships in these subjects. People like Edmund Sinnott, Ernest Babcock, Luther Burbank moved forward relatively unchallenged. I think this is because they clearly separated their work on improvement from any implication for human evolution and morality.

The one sticky point was eugenics, which many white scientists claiming European ancestry supported and most people in poor, rural communities in places like Tennessee rejected.

This was scientific engineering either at its best or worst, depending on your point of view. The Scopes Trial didn’t change anyone’s views about eugenics, but it highlighted their differences.

The main lesson to learn from the Scopes Trial is that sometimes scientists really don’t understand why people reject their ideas.

The supporters of Tennessee’s anti-evolution law weren’t narrow-minded fanatics. But neither were they focused on evidence-based arguments.

For them, academic science brought with it certain offensive values (scepticism, agnosticism, challenge, disrespect for authority), and it seemed to take away certain cherished parts of life (respect for elders, respect for tradition, humans are more than machines and units of labour).

Scientists didn’t understand that people’s objections focused on values, not fact.

Biotechnologists in agriculture know this problem well. When different publics encounter genetically modified cereals, for example, a lot gets thrown into the discussion, and sometimes it’s impossible to tease apart the technoscientific bits and the other bits.

However, we know those other passions can dominate discussions during engagement and that’s what happened in the Scopes Trial: being pro-evolution implied “monkey morality”. If we teach children they came from animals, they’ll think it’s OK to act like animals and they’ll reject the morality of their parents.

When William Jennings Bryan preached he ‘cared more for the Rock of Ages than the Age of Rocks’, this is what he meant: morality over science, every time.

Science communication is rarely about distributing technical information to non-technical people or translating technical information into easier-to-digest formats.

We have to appreciate how the receivers understand the world around and how they are going to assimilate what they learn into the understanding of the world they already have”.

Watch the Innes Lecture 2020

About Professor Joe Cain

A historian of science in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Professor Cain’s research focuses on evolution, both as a science and as a subject of public study.

Examples of his research include the creation of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs in the 1850s, the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial, and the history and legacy of eugenics. He currently leads the Legacies of Eugenics project at UCL.

Image reproduced from Literary digest July 25, 1925 under creative Commons 2.0 Generic license