The 2018 Innes Lecture; Citizen Science

The 2018 ‘Innes Lecture’ took the theme of ‘citizen science’.

Titled ‘Networks of Naturalists: Scientific communities in the 19th and 21st centuries’, Sally Shuttleworth and John Tweddle explored the history behind popular participation in natural knowledge and mapped today’s landscape of ‘citizen science’.

There are now over 450 natural history groups in the UK, who interact with experts, produce local atlases of flora, gather data that chart the impact of climate change, and contribute to national biodiversity surveys.

Nationally, over 70,000 people spend their free time recording species every year.

The volume of these contributions is staggering, for example John, who is Head of the Angela Marmont Centre for UK Biodiversity and Programme Lead for ‘citizen science’ at London’s Natural History Museum, was able to show us the geography of 1,160,000 observations made within 10km of the John Innes Centre, relating to 6,900 species.

You can see (and get involved) with this collaborative effort in a number of ways. The National Biodiversity atlas is an online tool produced by the National Biodiversity Network championing the sharing of biological data in the UK since 2000.

Previously the Orchid Observers Project invited volunteers to photograph wild orchids ‘and annotate museum specimens to contribute to climate change research at the Natural History Museum’. In this project over 4,000 museum specimens yielded data on orchid flowering times, but extracting the information required crowdsourcing.

As such, ‘citizen science’ projects are often billed as helping researchers deal with the flood of data confronting them.

‘Citizen science’ originated at Cornell University, in the USA, in the 1990s when members of the public were invited to join in and assist university science projects.

The concept has taken off in the UK in the last decade, with John describing it as a citizen science ‘revolution’.

The popular platform Zooniverse helped ‘citizen science’ hit the headlines after media coverage of its first crowd-sourced project ‘Galaxy Zoo’, which invited anyone with an internet connection to classify galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. By April 2009, more than 200,000 volunteers had made more than 100 million galaxy classifications.

The participation of ‘citizen naturalists’, enabled by digital technology, is particularly strong in the UK, from seaweed mapping to earthworm or our own slug watch.

This high level of national commitment to natural history is partly the legacy of the national biological recording schemes that have grown up in the 20th and 21st centuries, including the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI).

Sally, who is Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford, highlighted how the roots of today’s public engagement with natural history projects go back to the 19th century, citing Charles Darwin’s correspondence network of over 2,000 people, including amateur naturalists, farmers and keen gardeners, as an example of how elite scientists could recruit assistance from a surprising number of sources.

Darwin often used columns in popular periodicals to conduct this correspondence, for example, the ‘Gardeners’ Chronicle’. Our own founding Director William Bateson later gleaned many facts on ‘heredity and variation’ from the same source and consequently we have an excellent run of this title in our rare books collections, as the periodical was part of Bateson’s essential reading.

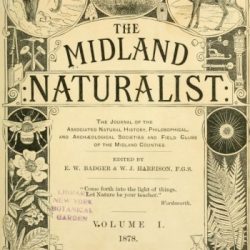

Alongside Darwin’s network, other networks of naturalists sprang up in the 19th century helping university botanists, entomologists and ornithologists chart geographical distribution of species, and spot unusual variations.

These groups also helped generate a popular consciousness of, and pride in, local and regional flora and fauna, while at the same time raising awareness of the disappearance of species and other changes brought about by modern agriculture.

As another example of 19th century ‘citizen science’, Sally highlighted the ‘British Rainfall Organisation’ founded by George J Symons in the 1860s, which had more than 3,400 reporting weather stations by the turn of the century. Being a rainfall recorder was open to any age, sex, or class and part of the organisation’s appeal was the chance to contribute to a national data set. Their reports are still available on the Met Office’s website.

Sally is currently leading a large research project, in partnership with the Natural History Museum, on ‘Constructing Scientific Communities: Citizen Science in the 19th and 21st centuries’, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

This project will bring together historical and literary research in the 19th century with contemporary scientific practice, looking at the ways in which patterns of popular communication and engagement in 19th century science can offer models for current practice.

Alongside the Innes Lecture, there was a display of our rare books and archives from the rich collections of the John Innes Centre, charting public involvement in natural history from the 19th century to the 1950s, including some of the original Darwin letters mentioned above.

The display illustrated that the popularity of natural history was sometimes a problem (for example, the disappearance of rare ferns following the Victorian ‘fern craze’) and sometimes a solution (for example the formation of Associations for the protection of plants which helped protect endangered species).

There were also examples of 18th and 19th century regional and local floras, documenting the contributions of amateur field clubs and botanical societies, among others.

This passion for identifying and recording species helped to raise awareness of profound changes in Britain’s natural environment.

For example, botanist Charles Babington prefaced his ‘Flora of Cambridgeshire’ (1860) with the comment; “it seems highly desirable to record not merely the present state of our Flora but also the great alterations caused by modern enclosures and drainage: alterations still advancing so rapidly that probably many of the places in which I have myself gathered plants within the last few years do not now produce them”.

Finally, some of the archives of the ‘British Rose Survey’ were on display – an example of a mid-20th century ‘citizen science’ project.

The organiser, Sheffield geologist P C Sylvester-Bradley, used schools and natural history networks to mobilise teams of volunteers for his project, to chart the native species of roses growing wild in Britain. The project was piloted in 1953 with the help of staff at John Innes who at the time were keepers of the National Rose Species collection.

If we had space for one more example we would have added genetics: Bateson’s information on heredity and variation in the early 20th century was drawn from a broad social spectrum that included horticulturalists, breeders, and professional scientists.

The Genetics Society, which is celebrating its centenary in 2019 and was founded by Bateson and Edith Rebecca Saunders, was born out of the interest of private individuals, and plant or animal breeders.

It is worth remembering that in those days there was a minority involvement of universities and as late as 1939, the percentage of Genetical Society members from universities was only 28%.

The Innes Lecture was introduced by the Director, Professor Dale Sanders, and by John Innes Foundation Chairman Peter Innes. It is a free annual public lecture on the history of science, and is a Friends of John Innes event.