Revealed; A 110-year-old secret about one of Mendel’s rediscoverers

In 1985 our History of Genetics Library gained a new book; a duplicate copy of the first edition of William Bateson’s ‘Mendel’s Principles of Heredity: A Defence’, published by Cambridge University Press in 1902.

No fanfare that we can find accompanied the addition of this copy to the shelves. The Accessions Register from the time records it as being purchased from bookseller F. E. Whitehart for £55, but there is no record of who suggested the purchase.

Despite an inauspicious arrival, this was a special book and of far greater value than the two existing copies in the Library it joined, for the first page of the book clearly bears the stamp ‘Professor Dr Erich Tschermak, Wien, XIX. Hochschule für Bodencultur’ (now the University of Agricultural Sciences Vienna) and the date June 1902. Furthermore, the work also bears Tschermak’s signature and is heavily annotated throughout, so it is almost certain that the Librarians of the day recognised the significance of this book to the story of Mendelism in Britain.

Over three decades on, we’d like to take this treasure down from the shelves and open it up to a wider audience, explaining why it is so special, and to invite readers to examine the pages for themselves.

First, it’s worth explaining who Erich Tschermak was. Better known now as Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg, the owner and annotator of this book has gone on to be dubbed ‘the father of Austrian plant breeding’.

Aged 30 in June 1902, Tschermak was nearly five years into his scientific career when he took ownership of this book. By now he’d already published his thesis on the inheritance of seed colours and shapes in pea hybrids (his ‘Habilitationschrift’) back in January 1900, and his career was progressing towards an Assistant Professorship (1903) at the Hochschule where he was engaged in cereal breeding, especially the problem of combining earliness with high yielding performance. So impressed was the Hochschule with him, in 1906 they created a separate ‘Chair of Plant Breeding’ role especially for him, making him the first Professor of Plant Breeding in Europe.

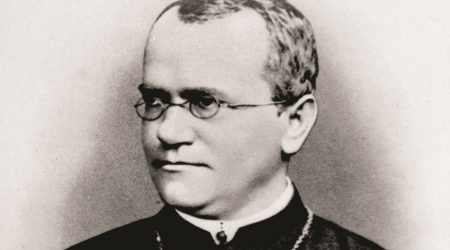

As impressive as these achievements were, it was Tschermak’s early work and its relationship to the work of an earlier experimentalist, Augustinian monk Gregor Mendel, in the monastery garden at Brno, Moravia, that had first established his reputation and made the Tschermak name a famous one in scientific circles.

Tschermak regarded himself, and was regarded by others in the early 20th century, as one of the three independent ‘re-discoverers’ of Gregor Mendel’s ‘principles’ of heredity (alongside German botanist Karl Correns and Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries). All three men published work in 1900, responding (all in different ways) to a paper by Mendel titled ‘Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden’ (Experiments on Plant Hybridisation) which gave the results of eight years of crossing experiments with 22 true-breeding varieties of the garden pea, Pisum sativum L.

The ‘principles’ derived from Mendel’s paper have been considered the foundation of modern genetics ever since, and the story of Mendel’s ‘rediscovery’ is one of the most popular and most debated in the history of science.

Tschermak, for his part, had not adopted all of the elements of ‘Mendelian’ understanding of heredity. Nevertheless, he was lauded by his contemporaries as one of the three scientists involved in bringing Mendel’s important work before the world (and later his role was commemorated in a variety of ways, including awards of university honorary doctorates, honorary memberships of elite scientific institutions, and an editorial in the Journal of Heredity which introduced him (in 1951) as ‘the last surviving re-discoverer of Mendel’s research in the genetics of the garden pea’ (see Ruckenbauer 2000).

Tschermak was also among the eminent European scientists (which included William Bateson, who went on to become Director of the John Innes Horticultural Institution) who travelled to Brno in 1910 to attend the unveiling of a statue to honour Mendel. On this grand occasion it was announced that Tschermak and Bateson were to be made honorary members of the Natural History Society of Brno.

Reputation, however, is a malleable thing, and from the 1960s Tschermak’s relationship to Mendelism began to be re-examined.

Some historians argued that Tschermak should be dropped from the realm of Mendel heroes, on the grounds that he misunderstood fundamentals of Mendel’s arguments and interpreted Mendelian phenomena within a pre-Mendelian concept of heredity.

Tschermak held ambivalent positions on the Biometrician-Mendelian disputes (see below), and his theoretical approach shared some common ground with an earlier Galtonian science of heredity, which was concerned with the regularly decreasing hereditary contribution of ancestors.

More recently historians have emphasised Tschermak’s career as a plant breeder to explain why his views on hybridisation as presented in 1900 differed from those of scientists working within traditions of experimental botany.

For example, Tschermak did not explain 3-to-1 ratios in the F2 generation in terms of segregation but in terms of unequal hereditary strength or influence; he was initially reluctant to adopt Mendel’s combinatorial conception of heredity, and his core interest as a plant breeder was the ‘potency’ or strength of each plant trait of commercial value. Such knowledge could be used by breeders, indicating whether a trait would breed true following the F2 generation, and if not, how long a hybrid would need to be inbred before the trait became stable (see Harwood 2000).

Then, in 2011 Simunek et al. added yet another layer of complexity to the story of Erich Tschermak when they published their study of the letters preserved in the Tschermak family archives (14 pieces of correspondence between 1898 and 1901), and of a significant collection of Tschermak letters catalogued and opened to researchers for the first time in the summer of 2009 in the Archives of the Austrian Academy of Sciences of Vienna.

These new sources revealed something that had remained a secret for more than 110 years; the extent of the involvement of Erich’s older brother Armin in the development of his theoretical ideas on heredity.

Their detailed work on the relationship between these two siblings suggests that perhaps we should acknowledge Armin as a ‘fourth’ re-discoverer of Mendel. Armin was one year older than Erich and already a successful physiologist (from 1906 holding a university professorship in Vienna).

The archives revealed how Armin had mentored Erich in his career choices from very early days and step-by-step guided Erich into an academic position, providing advice on research topics, recommending reading and, most importantly, discussing Mendel, de Vries and Correns with him. Armin also steered Erich’s published contributions, counselling him on how to present his work for maximum impact.

Our own book is further evidence of the close collaboration between the two Tschermak brothers, which features annotations that have been identified by an expert on the Tschermaks’ handwriting as belonging to both Erich and Armin (M. Simunek in 2009). Intriguingly it is Armin’s commentary that remains clear on the pages while Erich’s notes are mostly either erased or illegible.

Through the annotations we also find the Tschermaks’ privately engaging with William Bateson’s polemical defence of Mendel published in March 1902.

Bateson, a Cambridge zoologist turned experimental botanist, was the key scientist in Britain guiding what would soon be called ‘genetics’, the fledgling science started by the re-publication and re-interpretation of Mendel’s paper.

He first publicly introduced Mendel’s work (a digest of an account of it he’d read in a paper by Hugo de Vries) in an address to the Royal Horticultural Society on 8 May 1900, and it was in the RHS Journal that Bateson provided the first English translation of Mendel’s 1865 paper from the original German with an introductory note (the initial translation was by C. T. Druery, see Cock 1980).

Bateson’s need to ‘defend’ Mendel with this short follow-up book in 1902 originates from his very public squabble over the territory of heredity with British zoologist and former Cambridge friend W F R (Raphael) Weldon, a bitter controversy that has become another set-piece in the history of science, becoming known as the ‘Mendelian-Biometrician dispute’. At stake were the rival scientific tools and methods scientists used to approach the study of heredity and behind these, divergent theories about the biological processes driving evolution.

The ‘Mendelian-Biometrician dispute’ is a good example of historian Jan Sapp’s wider argument that Mendel became for the 20th century ‘a cultural resource to assert the truth about what it means, not just to be a good scientist, a geneticist, but what Mendelian genetics implies’ (Sapp 1990).

According to Robert Olby, the fundamental point Bateson took from Mendel was ‘the “purity of the germ cells” and the combinatorial processes that ensued’, which contrasts markedly with Tschermak, who as we’ve seen, did not initially adopt this combinatorial concept of heredity. Olby adds that Bateson’s Mendel was ‘clearly coloured by his opposition to the scientific credentials of late nineteenth century Darwinian research’ (Olby 1997, p. 12).

We know from other evidence that the Tschermaks both disliked the polemical way William Bateson conducted his debate with the biometricians, and that Erich Tschermak found himself between the quarrelling parties, with Weldon and his ally Karl Pearson as well as Bateson corresponding with him in 1902 (see Simunek et al. 2012).

The inscription in our book, indicates that Erich had acquired a copy of Bateson’s Defence before Pearson wrote to ask him to review Bateson’s publications on 11 July 1902, especially his Defence. Pearson originally wanted to publish Tschermak’s review in Biometrica, but it never appeared in that journal (perhaps being considered too neutral or pro-Mendelian). Simunek et al. speculate that Tschermak’s manuscript was used in his later published studies (Tschermak 1902, 1905, 1906).

Tschermak’s surviving correspondence with Bateson begins with a letter from Bateson dated 2 September 1902, and Bateson clearly regarded Tschermak as a supporter (and one of the re-discoverers of Mendel). They would go on to exchange occasional and friendly letters until 1925.

Armin and Erich’s annotations on Bateson’s Defence provide a fascinating additional insight into how the Tschermaks read Bateson and responded to the debates on heredity that were taking place in England at that time.

Most of their attention focused on the two parts dealing with ‘The problems of Heredity and Their Solution’ (pp. 1-39) and ‘A Defence of Mendel’s Principles of Heredity’ (pp. 104-208). By studying their engagement with the text, we can gain information on where they fundamentally disagreed with Bateson and glimpse their own developing theory of ‘cryptometry’ (see Simunek 2012, pp. 249-50).

We hope this unique book in the John Innes Foundation Historical Collections will prove of interest to historians of Mendelism and early 20th century theories of heredity around the world.

Below is a sample of the annotated pages. To see more of the annotated pages, contact sarah.wilmot@jic.ac.uk;

Top image caption – William Bateson and Erich von Tschermak at the IVth International Conference on Genetics, Paris, 1911 (from William Bateson’s Library, John Innes Foundation Historical Collections). This was probably their fourth meeting: Bateson met Tschermak in Vienna in 1904, in London at the International Conference on Hybridisation and Plant Breeding in 1906, and at the MendelFest in Brno in 1910.

Further Reading

- Allen, G (1975). Life sciences in the twentieth century. Wiley: New York

- Bateson, W (1901). ‘Problems of heredity as a subject for horticultural investigation’, Royal Horticultural Society, 25: 54-61

- Bateson, W. (1907). Discussion, p. 283 in Wilks, W. (ed) Report of the third international conference on genetics [1906]. London: Royal Horticultural Society

- Bowler, P (1989). The Mendelian revolution. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

- Bowler, P (2000). ‘The rediscovery of Mendelism’, pp. 1-14 in Peel, R and Timson, J (eds), A century of Mendelism. The Galton Institute: London

- Cock, A (1980). ‘William Bateson’s pilgrimages to Brno’, Folia Mendeliana, 15: 243-250

- Cock, A (1982). ‘Bateson’s impressions of the unveiling of the Mendel monument at Brno in 1910’, Folia Mendeliana, 17: 217-223

- Cock, A and Forsdyke, D (2008). Treasure your exceptions: the science and life of William Bateson. Springer: New York

- Corcos, A, Monaghan F (1986a). ‘Tschermak: a non-discoverer of Mendelism I: a historical note’, JH, 77: 468-469

- Corcos, A, Monaghan F (1986b). ‘Tschermak: a non-discoverer of Mendelism II: A critique’, JH, 78: 208-210

- Corcos, A, Monaghan F (1990). ‘Mendel’s work and its rediscovery: a new perspective’, Plant Science, 9: 197-212

- Dunn, L (1965). A short history of genetics: The development of some of the main lines of thought: 1964-1939. McGraw-Hill: New York

- Fairbanks, D and Rytting, B (2001). ‘Mendelian controversies: a botanical and historical review’, American Journal of Botany, 88: 737-752

- Harvey, R (2000). William Bateson and the emergence of genetics, a biography in five volumes. Unpublished; John Innes Centre Library, Norwich

- Harwood, J (2000). ‘The rediscovery of Mendelism in agricultural context: Erich von Tschermak as plant breeder’. R. Acad. Sci. Paris. Life Sciences. 323: 1061-1067

- Iltis, H (1911). ‘Vom Mendel denkmal und von seiner Enthüllung, Verhandlungen des naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn, 49: 335-363

- Mendel, G. (1866). Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden. Verhandlungen des Naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn. 3: 3-47. [Read 8 Feb and 8 March 1865] Translated in Stern and Sherwood (1966), see below.

- Punnett, R C (1950). ‘Early days of genetics’. Heredity, 4: 1-10

- Olby, R (1985). Origins of Mendelism, 2nd University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Olby, R (1988). ‘The dimensions of scientific controversy: the biometrician-Mendelian debate’, BJHS, 22: 299-320

- Olby, R. (1997). ‘Mendel, Mendelism and Genetics’, Available on Mendelweb

- Roll-Hansen, N (1980). ‘The controversy between biometricians and Mendelians: a test case for sociology of scientific knowledge’, Soc Sci Inf, 19: 501-517

- Ruckenbauer, P (2000). ‘E. von Tschermak-Seysenegg and the Austrian contribution to plant breeding’, Vorträge f Pflanzenzücht, 48: 31-46.

- Sapp, J (1990). ‘The nine lives of Gregor Mendel’, pp. 137-166 in H. E. Le Grand (ed), Experimental Inquiries. Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht. Available on Mendelweb

- Simunek, M, Hossfeld, U, Wisseman, V (2011). ‘Rediscovery” revised – the cooperation of Erich and Armin von Tschermak-Seysenegg in the contect of “rediscovery” of Mendel’s laws in 1899-1901, Plant Biology. Stuttg. 13: 835-41

- Simunek, M, Hossfeld, U, Breidbach O (2012). ‘Further development” of Mendel’s legacy? Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg in the context of Mendelian-biometry controversy, 1901-1906’, Theory in Biosciences, 131: 243-252

- Stern, C and Sherwood, E (eds) (1966). The origins of genetics: a Mendel source book. W.H. Freeman, San Francisco

- Stern, C and Sherwood, E (1978). ‘A note on the “three rediscoverers”’, Folia Mendeliana 13: 237-40

- von Tschermak-Seysenegg, E (1902). ‘Der gegenwärtige Stand der Mendel’schen Lehre und die Arbeit von W. Bateson’, f.d. landwirt. Versuchsw in Österreich, 5: 1365-1392

- von Tschermak-Seysenegg, E (1905). ‘Die Mendel’sche Lehre und die Galton’sche Theorie der Ahnenerbe’. ARGB, 2: 663-672

- von Tschermak-Seysenegg, E (1906). ‘Ueber die Bedeutung des Hybridismus für die Deszendenzlehre’. Biol Zentralbl, 26: 881-888

Bateson-Tschermak correspondence

Sadly, there are no original letters between William Bateson and Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg in the John Innes Foundation Historical Collections.

We hold photocopies of three letters, part of the Bateson collection in Cambridge University Library (all from ETS): 26 April 1910; 6 Sept 1910; 14 September 1910.

The John Innes reprint collection includes a significant collection of presentation copies of ETS publications, 1900-1926, eleven of these are lightly annotated by Bateson.

Third party correspondence with mentions of ETS in our Bateson Letters Collection may be located using the William Bateson Letters Database type ‘Tschermak’ in the subject field

There are 17 letters from William Bateson to Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg in the Archive of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna: 2 Sept 1902; 1 Jan 1903; 19 Dec 1903; 7 Dec 1904; 6 Jan 1905; 15 Feb 1905; 30 March 1905; 4 Jan 1906; 11 Oct 1906; 30 Oct 1906; 8 Jan 1907; 30 Dec 1909; [18 Sept 1910?]; 1 Nov 1910; 26 Feb 1922; [? 1900s, incomplete]; [July-December] 1925.

If anyone knows of any more surviving Bateson-Tschermak correspondence, get in touch.