Microbial science inspires immersive digital art

An internationally acclaimed artist, Henry Driver, has created an interactive digital artwork ‘Secrets of Soil’ taking inspiration from microbial research here at the John Innes Centre.

Henry is a young artist based in Suffolk who has shown work across the world and in galleries such as Tate Liverpool and the Barbican.

Earlier this year he was commissioned by BBC Arts and Arts Council England to create a digital artwork, “I wanted to try to capture some of the wonder I feel when I read about soil and the life that it contains”.

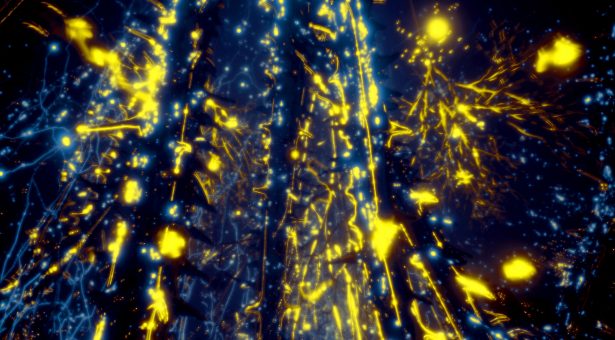

His interactive artwork is an ever-changing landscape of fungi, bacteria and other microscopic organisms and plant material, and shows how nourishing life in the soil can help the fight against climate change.

We spoke to Henry to find out more about the process behind the innovative artwork and the science that helped inspire it.

To learn more about the soil and microbes that inhabit it Henry met with some of our world-leading researchers in microbial science, who study many different microbes from multiple perspectives.

Henry had previously met with and used imagery from John Innes Centre researchers whilst working on other artistic projects such as REGENERATE and SYMBIOSIS.

These previous interactions with research at the John Innes Centre helped spark the idea for ‘Secrets of Soil’.

“I think from meeting John Innes Centre researchers during these projects I became interested in what’s happening in the soil, all the life that it contains as well as what we can learn from it. But also how looking after the soil better could be really helpful for biodiversity and carbon sequestration.”

“I thought visualising the concepts as 3D interactive worlds where people can actually see into the soil would be exciting. A teaspoon of soil contains a billion bacteria, but what does that actually look like? I really wanted to inspire people to think differently about soil – that it is a massive ecosystem. I think it can be difficult for people to care about something if they don’t empathise with it. So that was the drive behind it.”

To find out what life in the soil looks like, Henry met with a range of our researchers whose work span soil processes, bacteria, fungi and natural products.

“I was previously in contact with Henry from his project REGENERATE. I shared some microscopy photographs of mychorrhizal fungi and we talked a lot about symbiosis,” explains Dr Catherine Jacott.

To learn more about the bacteria that live in the soil, Henry also met with Dr Jacob Malone and a PhD student from his group, Alba Pacheco-Moreno.

Jake says, “I described the various microorganisms in the soil including their interactions and particularly bacteria over the course of a few initial conversations, then read through several drafts of the script and commented on scientific accuracy.”

Together with speaking to Professor Anne Osbourn, and Dr Dewei Wu about their work on how plants shape the soil microbiota and Dr Maria C. Hernandez-Soriano, a Soil Chemist from the Tony Miller lab, Henry started to piece together a picture of life in the soil.

“It was such an amazing experience speaking to all the researchers. It had such a big impact on me. However it took a while to work out how to visualise so many different areas of research, and how to make them seem alive”, reflects Henry.

“My initial idea was to make 3D models and then use cut-outs of the research imagery but that didn’t seem to work so well. So, I used colours from them or made similar textures. Seeing the fluorescence in some images Maria showed me inspired some of the colours used in the work.”

“Whereas from some research images I tried to turn them into a 3D form. For example, I spoke to Jake who described how certain bacteria look and move. Sometimes I was taking loose inspiration from the research imagery and other times I was trying to be quite close to it”, explains Henry.

Along with meeting researchers, Henry did further research, “I spoke to farmers discussing regenerative and intensive practises, and also consulted scientific publications to help expand my research.”

“I wanted to include so many things, that was one of the most difficult challenges; I had to cut out quite a bit. I had the idea for people to make their own soil, so it was going to be like the Sims but with soil so you can make your own soilscape. But technically that ended up being unachievable within the time frame,” reflects Henry.

Despite the challenge of so much information, Maria points out the success of the work, “It’s a tremendous effort that Henry has brought so many aspects together”.

“It was so exciting because when we’re looking at the particular microorganism we work on we don’t always see or think about the other microorganisms in the soil. It was stimulating to see representation of a much bigger picture and potential interactions between microbes,” says Cat.

Along with realising how much life is in the soil, Henry was also struck by how much remains to be discovered, “I found it surprising how much we don’t know about the soil.”

Cat comments on the parallels with scientific practice, “That happens for me too, from a scientific point of view. Sometimes you assume a concept is well-known or must have been researched before and then you start to look into the literature, and you realise actually there’s so much we still don’t know.”

“There’s lots of topics like that like root exudates, about which we really don’t know much in depth yet. It’s going to take some years before we get a good grasp on it and can act on it,” explains Maria.

Another challenge Henry faced was how to convey our impact as humans on the soil, “I wanted to think about how we affect the soil, about intensive agriculture and where we can go from there. That was actually the most difficult part of the work.”

Henry explains further, “I wanted to not be too anti intensive farming because obviously it’s brought huge benefits by supporting increasing populations and reducing hunger, poverty and malnutrition. I wanted to give a rounded view saying that it’s been helpful but now we realise we can’t do that anymore; we need to update. Jake’s comments and insights upon the script were really helpful with trying to strike this balance.”

The end of the work features activities you can do at home to improve the soil. “I wanted the work to be enjoyable but equally educational and accessible. I love galleries but unless you’re getting to the top it’s to a specific or limited audience and I love the idea of art being accessible and hopefully having an impact”.

Henry also met with Dr Jenni Rant from the Science Art and Writing (SAW) Trust who offered input into making the content more accessible to a non-science audience. Jenni reflects, “ I think his approach combining excellent graphics in a intriguing video really does bring the soil to life in a way that mirrors the life we see above ground and so will hopefully encourage people to be more mindful/respectful to the way they treat soils.”

“It’s exciting to see it reach different people. For example, on the Steam gaming platform there is a really in-depth review of the artwork in Russian, while the other week I was showing the work to farmers,” says Henry,

Commenting on the work, Dewei says, “To see artwork illustrate the rhizosphere space from an artist’s view is amazing and inspiring”.

Maria adds, “As a scientist I’m very grateful for the effort, to show people the wonder of the world of soil.”

Looking ahead, Henry reflects, “After the last two and half years of creating these projects and working with researchers at the centre, the work that I want to make is linking research, industry and the general public together, so that combined, we can try and create a better tomorrow.”