Gardening for Butterflies

This year’s Heritage Open Day event for the John Innes Historical Collections was an opportunity to show off some of the entomological treasures in our Rare Books Library.

The audience was also treated to a talk by Dr Ian Bedford, Head of the Entomology Facility at the John Innes Centre on ‘Gardening for Butterflies’. Ian’s scientific career spans 41 years, but his interest in butterflies and moths began far earlier, on childhood excursions to the South Downs in Sussex.

Ian began with a discussion of the evolution of the Lepidoptera 200 million years ago, the group that both butterflies and moths belong to. Prehistoric examples have been discovered trapped in amber revealing that today’s butterflies have hardly changed since the days of their early ancestors, and are far older than previously thought

Features that butterflies and moths have in common include their delicate scaled wing structure, and their well-defined life-cycle which runs from egg, to caterpillar to chrysalis to adult (a process of ‘complete metamorphosis’). The caterpillars will shed their skin from four to six times before the chrysalis stage when they will pupate and as if by magic be transformed from an eating tube to an adult in a process that will see its cells shifting into a ‘soup’ before being reassembled.

Ian next gave some tips on distinguishing butterflies and moths. It’s a butterfly if it has all these characters:

- Flies during daylight

- Holds its brightly coloured wings in an upright position when at rest

- Has clubbed antennae

However, there’s always a few moth species that exhibit one or two butterfly-like characteristics…

In general, it’s difficult to tell the caterpillars of moths apart, although the really hairy and very large caterpillars will belong to a species of moth. Butterflies tend to hang the chrysalis under leaves or similar cover. Moths on the other hand have chrysalis’s underground or will be wrapped within a cocoon. Some species of butterflies have evolved really specialised lifecycles, for example, Large Blue butterflies have a symbiosis with ants and pupate in their nests. The ants protect the caterpillars from predators in return for a reward; the sugars the caterpillars secrete.

Ian also described some of the special senses butterflies have.

They can see UV light and polarised light thanks to special photoreceptors in their compound eyes. Most flowers have evolved UV patterning, and this helps lead the butterflies to their nectaries. Some butterflies also use visual signals (‘flashes’) from iridescent patches on their wings to attract the attention of females. For example, the Purple Emperor uses visual signals to attract females to mate high up in the forest canopy (oak and sallow trees). The males also eat nasty substances (for example, fox faeces) to obtain the chemicals they need to produce pheromones, another trick for drawing the females in from the surrounding neighbourhood.

Butterflies and moths use their antennae to detect pheromones and Ian gave the example of the Vapourer moth males who can detect female pheromones up to six miles away.

There are 58 or 59 species of butterfly in Britain and a few regular migrants and for all of them healthy habitats are essential, meaning they are vital indicators of failing ecosystems.

The impact of habitat change will depend on whether the species is a habitat generalist or a habitat specialist. The specialists are the most vulnerable. For example, butterflies adapted to meadow, heath and grassland (Gatekeepers, Ringlets, Meadow Browns, Marbled Whites and the Skippers, for example). Brown butterflies have only one generation and the caterpillars feed on grass, so the effects of drought can be devastating. Other specialists seek out woodland glades (Purple Hairstreaks, Purple Emperors, White Admirals, Silver-washed Fritillaries); Montane regions are habitats for the Mountain Ringlet and the Scotch Argus. Finally, wetland habitats in this region are home to the Swallowtail butterfly (Catfield Fen, Hickling Broad, How Hill, Ranworth Broad, Strumpshaw Fen and Wheatfen Broad – these are all good places to hunt for them between mid-June and early August), where their food plant is milk-parsley.

Ian warned that butterfly populations are in real trouble; overall numbers have halved in the last 40 years. Among the most dramatic falls are the Small Tortoiseshells (down 64%) and the White Letter Hairstreak (down 96%- its survival depends on Elm trees).

The problems butterflies face include habitat loss (over half of the hedgerows have been lost since 1947), climate change (which disrupts hibernation in overwintering adults), and adverse weather events which can immobilise adults and prevent them from breeding.

The widescale use of insecticides (particularly the Neonicotinoids) has also impacted on numbers. Neonicotinoids are systemic and persist in the environment for many years, dispersing through the ground water from seed-treated crop fields to contaminate the wild plants at the margins. A recent survey revealed that garden plants sold in nurseries are also often pre-treated with these chemicals, even when they bear the label ‘good pollinator’ plants.

How can we all help?

Ask your nursery before you buy plants for your butterfly gardens to make sure they haven’t been treated with systemic insecticides that will be harmful to butterflies, and always try to find a safe alternative to using pesticides in your own garden.

Consider changing your planting schemes with butterflies and moths in mind, ensuring that nectar producing flowers are present throughout Spring, Summer and Autumn.

Be aware though that butterfly species have different length tongues, so grow flowers suited to different types. For example, perennial sunflowers and wallflowers are very good for the short-tongued species, whilst buddleia is perfect for the long-tongued species.

You could also consider extending the nectar season: verbena and Russian sage are good choices for this.

You can also provide ripe fruit for the migrating butterflies to feed on; control spider predators by keeping the webs away from your butterfly borders; and you could plant patches of food plants for their caterpillars (for example, Ivy, Bramble, Buckthorn, fescue grasses, garlic mustard, cock’s foot, nasturtium, and nettles- though you need a large patch in the sun for this to be effective).

Butterflies and moths also need winter refuge, so try not to cut back shrubs and perennials until the spring. Leaving a pile of logs in a sheltered spot will also be good for hibernating butterflies such as Peacocks to overwinter within.

Ian concluded his talk with a few good news stories about our butterflies.

Comma Butterfly numbers are up 138% compared with 40 years ago and they appear to be thriving on nettles as their primary host plant. The White Letter Hairstreak is returning to old sites (low elm hedges). The Silver-washed Fritillary was sighted at Ashwellthorpe wood this year for the first time in 30 years and is also back at Strumpshaw Fen.

There are also new butterfly conservation projects trying to address the falls in numbers. To find out more about national and local initiatives and to get more advice on the best nectar plants for butterflies and moths, visit the Butterfly Conservation website.

After the talk visitors toured a display of butterfly and moth illustrations from the John Innes Centre Rare Books collection.

John Innes Rare Books display

The display was divided into themes, beginning with butterflies and moths in botanical illustration. This section featured three examples from Europe. The first was the work of Dutch engraver Crispijn van de Pas. His Hortus Floridus (a very rare 5-parts-in-one volume), published in 1614 and showing how he incorporated butterflies within some of his copperplate engravings. While the flowers have a high degree of accuracy, the butterflies he depicted are more generalised and included more for artistic effect. This is also true of many of the butterflies included in the botanical illustrations commissioned by wealthy Nuremberg doctor Christoph Jacob Trew. His Hortus Nitidissimis is one of the outstanding florilegia of the 18th century. We also showed an illustration by Adam Ludwig Wirsing, one of the many celebrated artists employed in the making of this book. Wirsing worked in Nuremberg after 1760 and was famous for his natural history illustrations.

The final book in this grouping was Nederlandsch Bloemwerk, or Dutch floriculture, which showcased the spectacular tulips, hyacinths, auriculas, roses and other flowers that were coveted in the 18th century (rather like an up-market plant catalogue). The prints in this volume are unsigned but are thought to be by Paul Theodor van Brussel (1754-1795). Some of his hand-coloured engravings include stylised butterflies for artistic effect, but we displayed his illustration of a rose with associated insect life which recalled Dutch artist Maria Merian (1647-1717) and her more strictly entomological studies.

All three represented an artistic tradition in Europe of including insects as decoration within a botanical print, something that doesn’t seem to have been common in English traditions of plant illustration which focus more strictly on the plant specimen itself.

The next part of the display featured 18th century butterfly and moth studies.

Maria Merian’s work showed her fascination with the life-cycle of butterflies and moths, a study that she began at the age of 13. Though we take metamorphosis for granted today, this biological phenomenon was little known in her time. Her illustrations depict the different stages from egg to adult and show the insects together with the food plants on which they depend.

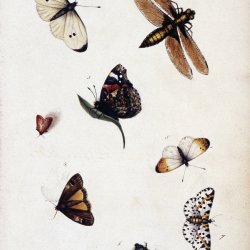

Merian’s careful studies inspired the German miniature painter August Johannes Rösel (1705-1759) to take up the study of insects, having discovered her work while he was recovering from an illness. We have the Dutch edition in our collection, De natuurlyke historie der insecten (Haarlem, c. 1765), a multi-volume work that shows why today Rösel is considered as one of the fathers of German entomology. He took from Merian a concern to depict butterflies and moths in all their life stages, but his approach was to display the insects in white space rather than artfully placing them within a plant illustration as Merian does.

Other parts of the display featured butterflies and moths in popular natural history books, with examples from the 19th to 20th centuries. This section included the wonderful (unpublished) watercolour insect studies of Anna Sophia Clitherow.

Although we have her sketchbook, which dates from c. 1804-1815, we know very little about her life beyond that she lived in a modest country house in Hertfordshire (near Bayfordbury) and died in London a spinster.

Her studies, which also show her interest in Linnaean botany, give a fascinating glimpse into some of the paints available to natural history artists in that period. Dorothy Cayley’s unpublished sketches of John Innes characters in the early 20th century, including one of the first John Innes entomologist C. B. Williams setting off to collect specimens with his butterfly net, also attracted admirers.

The final section was devoted to showing the part that butterflies and moths have played in evolutionary studies and genetics, with works by Alfred Russel Wallace, William Bateson, Reginald Punnett and Leonard Doncaster. Wallace’s discovery of natural selection was inspired by years studying geographical distribution and variation in Malayan butterflies.

Bateson turned his childhood fascination with moths and butterflies to good effect in his own evolutionary studies (for example, he studied variation in the eye-spots on butterfly wings). Examples like these eventually inspired Bateson to move away from Darwinian explanations to seek answers in a new science of ‘genetics’.

Punnett was interested in butterfly mimicry, where one species mimics another in appearance for some adaptive advantage, while Doncaster discovered sex-linked inheritance while writing up the results of a study on the ‘Currant’ or Magpie Moth. He later went on to write several books on genetics, and this moth became a textbook example of how genes are linked to sex chromosomes.

Overall the books chosen for the display demonstrated the range of topics and books covered in our Rare Books and History of Genetics libraries, and we were delighted to welcome visitors to see them on this Heritage Open Day 2018.

To find out more about the entomology books in the John Innes Historical Collections contact Sarah Wilmot. Members of the public may access the collection by making an appointment with Sarah.