Near his home was a lake and when he wasn’t diving in, young Martin was on its banks casting a line as he nurtured a passion for angling

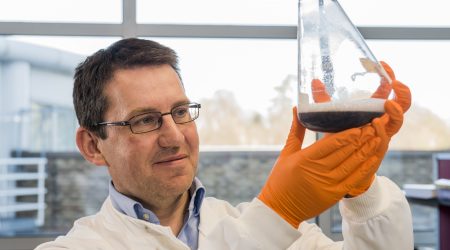

Arriving in Norfolk 17 years ago, Dr Rejzek, a natural product chemist at the John Innes Centre, struggled with life in a new landscape. So he set to work making a home from home.

Dr Rejzek joined the Norfolk branch of the Pike Anglers’ Club, the biggest single fish species interest group in the UK. He recalls the warm welcome from a group of “proper Norfolk chaps” who agreed to take him out on to the Norfolk Broads.

He says, “In a rowing boat you lose yourself in these awesome Broads, surrounded by reeds, the water and wild birds… At that moment, I became passionate about Norfolk.”

But it soon became clear that Norfolk pike angling was experiencing troubled waters.

Prymnesium parvum, the golden alga, is responsible for millions of fish deaths worldwide. Able to kill fish within hours, Prymnesium first causes chaos as the waters boil with the frantic activity of fish trying to escape. This is often the first sign of trouble from this stealthy killer, followed by thousands of dead fish clogging up the waterways.

John Currie, the general secretary of the Pike Anglers’ Club of Great Britain, says, “Before the first Prymnesium wipeout in 1969, the Broads was one of the most important pike fisheries in Europe. But people had heard tales of Prymnesium and had started to give up on the place.”

Fortunately, for the £550m Broads tourism economy, things would take a turn for the better. Dr Rejzek researched Prymnesium and discovered it produces the toxin prymnesin, which previous studies had shown to be a highly complex organic molecule.

Professor Rob Field, Project Leader at the John Innes Centre, recalls;

He describes the toxin as a “beast of a molecule”, a secondary metabolite with potential value as a natural product used for medicine and agriculture. “There were spin-offs in all directions: all sorts of biochemistry going on that we could use for industrial biotech.”

An important breakthrough came when the team noticed what Dr Rejzek calls “some bizarre dots” in samples of the alga.

These turned out to be a virus, which explained a mystery. The team had noticed that high Prymnesium cell counts did not necessarily lead to fish kills on their own. It was the presence of the virus, which at the end of its life cycle was causing cell lysis – with the alga spilling toxins into the water in one event – that was proving deadly.

Research continues to better understand the virus and the environmental conditions in which it flourishes. But for now, the greatest contribution of the John Innes Centre’s team has been in finding a quick, cheap and readily available way of mitigating Prymnesium outbreaks.

Research by John Innes Centre PhD student Ben Wagstaff and colleagues from University of East Anglia (UEA) revealed a candidate solution: hydrogen peroxide, the household chemical best known as hair bleach. “We developed a system in the lab using low enough concentrations that would kill algae but not affect fish or macroinvertebrates,” explains Dr Wagstaff. “Then we took our lab understanding and sprayed a very small section of Hickling Broad which had been affected by blooms, and it worked brilliantly.”

The breakthrough was hailed as a “lifesaver” by John Currie. “Thanks to this research we can save fish rather than observe them dying. To the local fishing fraternity, Martin and his colleagues at the John Innes Centre and UEA are heroes. It’s hard to put into words how important this is for us.”

It was also welcomed by the Environment Agency (EA), which has to pay the bill to deal with Prymnesium outbreaks. One operation to rescue 750,000 fish from Hickling Broad in 2015 took six weeks, costing just under £40,000 in staff time. “The John Innes Centre work on hydrogen peroxide shows how we can work together to translate research into real life,” said EA Fisheries Technical Specialist Steve Lane.

For Dr Rejzek, the Broads project speaks volumes about life in his lab and adopted landscape