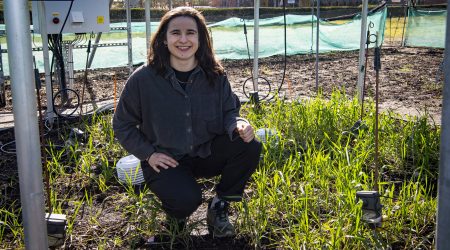

Wheat choice has lasting effect on soil health and wheat yield

Scientists investigating how to control take-all, a fungus that lives in soil and infects wheat roots to cause disease, have discovered that different varieties of wheat have distinct and lasting impacts on the health of the soil in which they are grown.

Researchers at the John Innes Centre and Rothamsted Research in Harpenden, examined the effects of growing high and low take-all building susceptible wheat on the make-up of the soil bacterial community associated with the second wheat crop. To their surprise, the impact on the soil from wheat grown in the first year of the experiment completely overrode any expected influence of the second year’s crop.

They found that the variety of wheat grown in year one sets the scene in the soil, and what is going on in the soil long after harvesting the initial wheat crop determines the subsequent year’s root health and yield.

Dr Jake Malone, of the John Innes Centre said:

“We knew that plants and microbes in the soil interact in a multitude of ways but we didn’t realise just what an impact growing different varieties of the same crop could have on the communities of microbes living in soil. We hope to take this further and define exactly how different wheat crops affect these important soil microbes.”

These findings point to new guidance for growers to choose the variety of wheat they grow in their first rotation carefully, as this will determine the soil health of the second wheat crop and could have long lasting effects on yields in subsequent years.

The research, funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), used a new approach to analyse microbes in soil, based on the statistical comparison of many bacterial genomes.

The team examined the abundance and the genetic structure of an important soil bacterium, Pseudomonas fluorescens. Different strains of this microbe are responsible for boosting plant growth and protecting crops against harmful diseases.

Both the amount of Pseudomonas in the soil, and the nature of the strains of this microbe present were strongly influenced by the type of wheat grown a year earlier. Growing wheat with a high associated level of take-all fungus led to a greater abundance of Pseudomonas, and seemed to select for bacteria that take an aggressive approach to other microbes, wiping out members of another soil dwelling bacterial species, Streptomyces, in laboratory experiments.

Meanwhile, growing a low take-all building crop resulted in the soil supporting the second wheat crop having lower overall levels of Pseudomonas, and selected for bacterial genes for iron scavenging and plant growth manipulation. Unsurprisingly, yield was higher following the low take-all building susceptible variety.

Dr Tim Mauchline from Rothamsted Research added:

“The finding that the footprint left from the previous year’s crop influences both crop yield and the soil-root microbial community structure in the subsequent year is fascinating, and offers potential as an exciting avenue of research to enhance crop protection.”

The team intends to expand their research to cover a five-year period, to examine how the community of soil microbes develops, and how the presence of the take-all fungus and the associated root disease affects the soil microbial community.

Ultimately, this research could lead to new approaches to control root diseases in cropping rotations, by choosing the right plants to grow at the right time in order to promote healthy soil and minimise the chances of disease outbreak.

For the study has been funded by the BBSRC and the University of East Anglia, the wheat variety rotation field experiment and the yield results were obtained on the arable Experimental Farm at Rothamsted Research as part of the Wheat Genetic Improvement Network (WGIN) core project which is supported by the Department of the environment and rural affairs (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs).

Professor Kim Hammond-Kosack from Rothamsted Research said: “This is an excellent example where a project funded for wheat genetic improvement has provided a useful resource for distinct analyses and deeper insight.”