How parasites keep the gene pool healthy

All life forms have depended on having a diverse range of genes in order to adapt and survive through the ages.

Research published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B reveals how parasites co-evolve with their hosts so that genetic diversity is maintained. Compromise between hosts and parasites is vital, say scientists at the John Innes Centre.

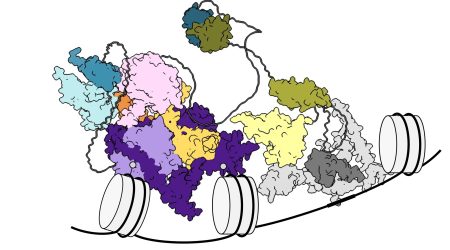

Researchers funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) have developed a mathematical model to examine how organisms can maintain their gene diversity for resistance to disease. The research highlights how a diverse gene pool helps plants and animals to deal with diseases, and how parasites, in return, use genetic diversity to overcome defences.

“The more diverse, or polymorphic, the organism is, the more it can adapt to its environment. One of the reasons for this genetic diversity is interaction between parasite and host,” comments Professor James Brown.

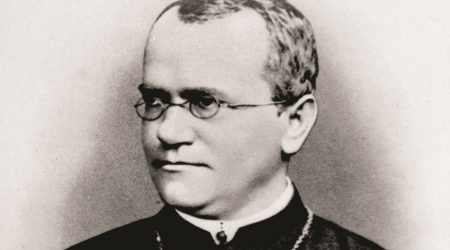

Despite millions of years of evolution where increasingly improved resistance to disease should be expected, plants and animals including humans are still susceptible to parasites in varying degrees. Aurélien Tellier, a PhD student working with Brown, proposes a general solution to this paradox with their mathematical theory.

Parasites constantly adapt to host organisms, and their hosts constantly evade attack by evolving resistance. But compromise is of the essence, according to Tellier and Brown. They show that when the rate at which the parasite adapts to its host slows down as parasite numbers increase, the genetic diversity in both host and parasite can be maintained. Eventually, the host and parasite arrive at a compromise, where the parasite ceases to become more virulent and the host ceases to become more resistant.

The theory predicts that many biological and ecological factors are likely to contribute to the compromise – for instance when several generations of the parasite survive in the host, or when plant seeds survive several years in the soil without germinating.

“Without these challenging factors in our environment we would most likely have lost genetic diversity a long time ago and become less able to cope with diseases,” said Brown.

Professor Julia Goodfellow, BBSRC Chief Executive, said: “This research gives us a better understanding of how we have genetically adapted to our environment, and contributes to our knowledge of disease resistance.”