Multicellularity: How and why cells communicate

Matthew Johnston is a Phd student in the Dr Christine Faulkner lab.

His research focuses on cell-to-cell communication in plants, so we asked Matt, how and why do cells communicate?

“Roughly 600 million years ago, the first multicellular organism evolved from single-celled life.

The rise of multicellular life gave multiple benefits to those organisms over their single-celled compatriots, with perhaps the most important advantage being specialisation.

Specialisation allows one part of an organism to become extremely good at doing one thing, such as forming teeth for biting, or leaves for photosynthesising; better than a single-celled organism could do it alone.

However, for multicellularity to be successful there must be transport and communication between cells.

Transport is required for the movement of resources around a multi-cellular organism. For example, our brains are great for thinking, but require oxygen obtained in the lungs, so there needs to be a way to get to from one to the other.

Communication is required for sharing information, in two senses. First, to alert the rest of the organism about one part’s requirements, “I need sugar over here” and to inform neighbouring tissues of each other’s state, “I’m a root, so you don’t have to be” or “Help, I’m under attack…”.

Much like their animal counterparts plant cells communicate in a multitude of ways, from chemical to electrical.

Communication in its most basic form occurs when cells detect any change of their environment.

A common form of communication between cells is the release of chemicals. These chemicals can be noxious, so as to directly elicit a defence response in neighbouring cells. Alternatively, they can be benign but are perceived by unique receptors within cells. An example of this, in animals, is oestrogen which is produced in the ovaries and is circulated in the blood and then diffuses into cells throughout the body, where it is perceived.

Not all hormones can diffuse directly into the cell and some require a specialised protein which can transport the chemical into (and out of) the cell. A classic example is auxin, the hormone responsible for driving plant growth.

However, not all communication has to be done by chemicals moving across membranes and back again.

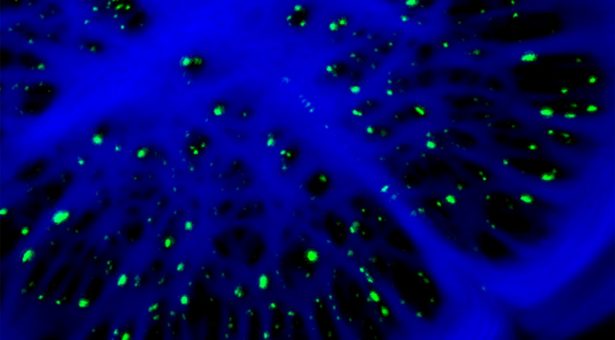

Plants have evolved tunnels which link cells directly through the cell wall. These are called plasmodesmata and they enable direct cell-to-cell communication.

Plasmodesmata can be used for both transport and communication and often these are same process. For example, transcription factors (proteins which modify what genes the cell is expressing) can be transported cell to cell via the plasmodesmata. Once transported to a new cell, the transcription factor then directly reprograms the cell to express different genes. These instructions for what genes to express, have been communicated by its neighbour.

Interestingly, movement through plasmodesmata can be coupled with movement by transporters, simultaneously as has recently been shown to be the case with auxin.

In the Faulkner lab, we explore how plasmodesmata function in plant defence.

When a plant cell comes under attack the plasmodesmata shut, closing the channels between plant cells. This has a knock-on effect, changing the communication between cells.

Lastly, not all communication has to be by small molecules and over short distances.

Plants, like animals, also use electrical signalling to transmit information over long distances very rapidly. For example, when a plant is wounded, say by a snail, rapid waves of calcium and electricity are sent along the plant to alert distant leaves that they may soon be eaten too. This, in turn elicits defence compounds to be made in leaves far away from the invader in preparation in an attempt to stave off further attack.

We may not hear it, but cells are constantly communicating to keep the plant alive”.