How do plants make starch?

Unlike humans, plants are not able to eat food in order to meet their energy needs, instead they have to make their energy by photosynthesis.

As every GCSE student can tell you, photosynthesis is the process through which light energy is converted into either chemical energy or sugar. When it is converted to sugar, that is in turn used by the plant for things like respiration, growth and reproduction. Some of the sugar is also stored for use later, by being converted into starch.

Plants make, and store temporary supplies of starch in their leaves, which they use during the night when there is no light available for photosynthesis. Many plants, including crop plants like wheat and potatoes, also make starch in their seeds and storage organs (their grains and tubers), which is used for germination and sprouting.

But what exactly is starch? Starch is a chain of glucose molecules which are bound together, to form a bigger molecule, which is called a polysaccharide. There are two types of polysaccharide in starch:

- Amylose – a linear chain of glucose

- Amylopectin – a highly branched chain of glucose

Depending on the plant, starch is made up of between 20-25% amylose and 75-80% amylopectin.

As well as being important for plants, starch is also extremely important to humans. Starchy food for example is the main source of digestible carbohydrates in our diet.

The structure of starch can affect digestibility, with high amylose being more resistant to degradation. As such, foods with high levels of amylose are an important source of ‘resistant starch’, which has the potential to provide a range of health benefits by lowering elevated blood glucose levels and insulin response to carbohydrate-based meals that are low in fibre.

Starch also has many non-food applications, including use within the papermaking industry (providing strength to paper), manufacturing of adhesives, the textile industry (as a stiffener), and the production of bioplastics.

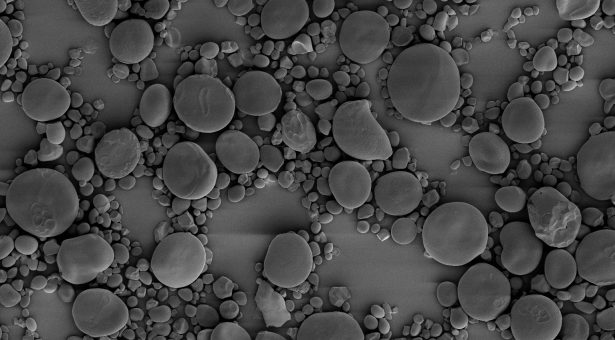

The many varied uses of starch depend on its structure, with granule shape and size affecting the properties of starch, and therefore its uses. For this reason, it is important for us to understand more about starch granules; including how starch polymer growth is directed, how different shaped and sized granules are formed, and how the plant controls the number of granules made.

A lot of our understanding about starch initiation and formation in leaves has come from work on the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

However, there is still a lot of work to do to understand granule initiation and formation within cereal grains. As cereals are one of the major food crops, and a major source of starch for industrial processes, understanding granule initiation and formation in grains is crucial.

At the John Innes Centre we are using a large mutant collection of wheat to investigate the granule initiation and have already isolated several promising mutants with radically altered starch granules. By investigating these further, we hope to identify key candidates involved in granule initiation in wheat, which may allow the development of new tools to improve crop quality and tailor starch production properties for different uses.