Help us transcribe a piece of genetics history

It might look unimpressive from the outside, but this small, student notebook from the John Innes Centre Archives could help change our understanding of the history of genetics in Britain.

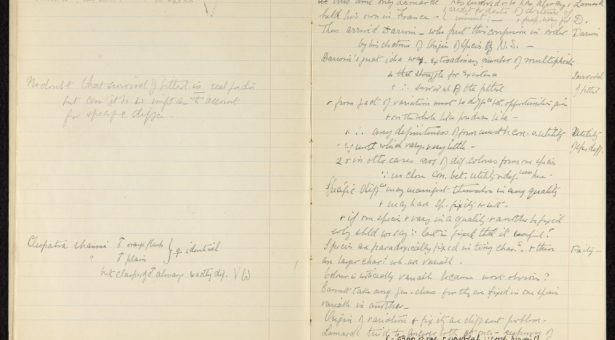

Its dull cover binds together notes from the first ever lectures on genetics in Britain, and records what William Bateson thought was important to pass on to students at this moment in the history of plant science, including who and what they should be reading.

We have recently digitised the 157 pages but we need your help to transcribe them. Until then we won’t be sure what this book might reveal.

Transcription means reading the original pages and then reproducing the text in type.

To celebrate the centenary of the Genetics Society founded by Bateson and E. R. (Rebecca) Saunders in 1919, we are making the digitised notebook and transcriptions publicly available, allowing people both to see the original pages and read a typed version of the text, without the difficulty of reading early 20th century handwriting.

We hope this project will open the notebook to new audiences, and encourage further study in the history of genetics and women’s education.

The notebook was donated to the John Innes Centre Archives in February 2010.

At the time, following the retirement of our previous archivist Rosemary Harvey, we lacked a professional archivist. As a stop-gap our archives were maintained but not studied by our library team.

I first became aware of the notebook through a Wellcome Trust Research Resources Grant project in 2016.

The notebook was written by Mary Gladys Sykes (1884-1943).

Mary was born in Chester to John Thorley Sykes, a cotton broker, and Mary Louisa March, MBE. Educated at home, Mary went on to study at Queen’s College, Chester, before earning a place at Girton College, Cambridge in 1902. Girton College was a women’s college deliberately sited well away from the existing (all male) colleges.

The notebook is 18cm by 23cm, and was divided by Mary into two parts (for convenience we’ve named them ‘Book 1’ (114 Pages) and ‘Book 2’ (43 pages) and begins with handwritten notes, on a lecture given by Bateson.

While there is no date recorded in the pages, we think the notes date from anywhere between 1907 and 1909.

It was during this period that Bateson was a Professor of Biology at Cambridge University, teaching an extra-curricular course titled ‘Heredity and Variation’. The very title of the course shows that the word ‘Genetics’ had not yet bedded in. Bateson however did use the term later on in the lecture and it appears, in inverted commas, in Mary’s notes. Bateson had originally coined the term a few years previously in a private letter to Cambridge zoologist Adam Sedgwick dated 18 April 1905.

In the second part of the notebook (the bit we’ve called ‘Book 2’), for reasons known only to Mary, she turns the book upside down and starts again.

Book 2 appears to be Mary’s reading notes concerning the history of biology, as understood in the early 1900s. We believe it may also include Bateson’s personal, anecdotal, take on some of the historical figures.

Mary had recently graduated with a Double First in the Botany Tripos (the name of the degree exams set at Cambridge University), although because she was female she was not awarded a degree, as was policy at the time.

Mary began her research career in botany at Newnham College. In the early days in this post she frequently returned to Girton to teach courses in Natural Sciences. She was also an occasional lecturer at the University’s Botany School and at Westfield College in London.

In 1910 Mary married one of her Cambridge collaborators, botanist David Thoday, and interestingly Mary never took up genetics.

Like her husband, Mary was more interested in plant morphology and physiology and the couple became rather hostile towards genetics after their student days.

Over her research career, Mary showed herself to be a versatile botanist, her expertise ranging across cytology, histology, and the anatomy and physiology of vascular cryptogams, including Psilotum, Tmesipteris, and some of the Gnetaceae.

She published her research in Annals of Botany and the Philosophical Transactions. Her career was sufficiently distinguished for Nature to publish a short obituary when Mary died in 1943.

Ironically, given their feelings towards genetics, Mary and David’s son, John Thoday FRS, became Arthur Balfour Professor of Genetics and Head of the Department of Genetics at Cambridge from 1959 to 1983.

Mary’s isn’t the only student record of Bateson’s lectures to survive; there is one kept by Nora Barlow but it is less detailed.

Nora was born Nora Darwin, granddaughter of Charles Darwin, and went on to study with Bateson when the ‘John Innes Horticultural Institution’ was based at Merton in Surrey.

Nora’s notes are preserved in Cambridge University Library’s collection of Darwin family papers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the archivists of Newnham and Girton colleges, University of Cambridge for information on the life and career of Mary Sykes, and Professor Marsha Richmond for information on Mary’s views on genetics.

The John Innes Centre would also like to acknowledge the vital role in the re-discovery of the notebook by the two project archivists employed through a Wellcome Trust Research Resources Grant in 2012-2013 and 2016-17.

Finally, we are indebted to the Thoday family for permission to publish the notebook’s pages online.