Snapdragons take the evolutionary high-road

Roses are red, violets are blue, but why aren’t snapdragons orange?

Norwich scientists from the John Innes Centre and the University of East Anglia (UEA) in collaboration with the Université Paul Sabatier (Toulouse, France) have developed a pioneering computer modelling technique that tracks the evolution of flower colour in snapdragon (Antirrhinum).

Their research, published in the prestigious journal Science, shows how flower colour has evolved in wild populations of these plants in the Pyrenees.

In the wild, only the plants with the most attractive flower colours are able to reproduce and thrive because the insects that pollinate them prefer certain colours.

The bees that pollinate snapdragon find magenta and yellow flowers the most attractive; they do not find colours such as orange attractive and so snapdragons of this colour would not flourish in the wild due to lack of pollination.

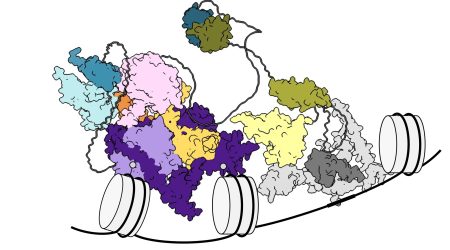

Scientists already know that natural colour variation is controlled by three genes. For this study the researchers wanted to understand how plants producing magenta or yellow flowers could evolve from a common ancestor without producing in-between non-attractive flower colours such as orange.

“This is a totally different way of looking at evolution and could lead to a better understanding of the rules that govern biodiversity” explains Coen, “If we can grasp how snapdragon genes interact in their natural habitat, it may help us in the future to better preserve genetic diversity”.

The team led by Professor Enrico Coen and Andrew Bangham (UEA) combined molecular, genetic and computational approaches to analyse flower colour variation in natural populations of snapdragon.

“We now understand how these plants can evolve to produce different colours whilst staying attractive to pollinating insects – we’ve found that colour can vary naturally but stays within defined limits” states Enrico Coen.

But if pollinators prefer certain coloured flowers, why aren’t all flowers the same colour? “We still do not know precisely why flower colours should vary in the first place,” says Coen, “it could be due to random genetic changes, or alternatively there could be an evolutionary advantage for certain colours in different environments”.

The researchers are now applying this new way of modelling evolution to other characteristics, allowing them to identify how apparently distinct traits are linked.