Exploring the inner world of carnivorous plants

Professor Enrico Coen from the John Innes Centre has been awarded €2.5M EU funding to explore the growth and evolution of carnivorous plants.

“Carnivorous plants turn the normal order of nature upside down, eating animals instead of being eaten by them,” said Karen Lee, a researcher working on the project at the John Innes Centre.

“They present us with a fascinating example of how new shapes and structures evolve in nature.”

Carnivorous plants grow cup-shaped leaves to catch their prey of insects, protozoa and even tadpoles and occasionally small mammals. The extra nutrients they acquire in this way allow them to live in nutrient-poor locations.

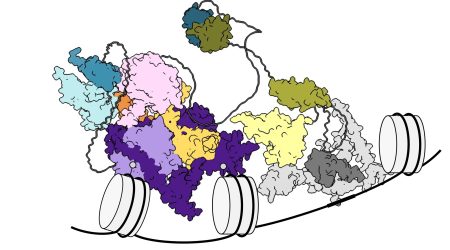

The John Innes Centre scientists have used 3D imaging techniques to give an inside view of these remarkable leaf structures. This is part of a new project to convey the inner world of plants through new imaging methods.

The carnivorous habit and the leaf shapes needed to trap prey have evolved repeatedly in independent orders of flowering plants. This suggests that relatively simple changes might be behind the evolution this complex form.

“To understand the origin of such forms, we need to know how they develop and how one form may be derived from another,” said Lee.

The researchers in Coen’s group will focus on a genus called Utricularia, commonly known as bladderworts.

They live in aquatic environments and obtain essential nutrients from water-fleas and protozoans in lieu of having roots. Leaves are shaped into vessels with a trap door and attached trigger hairs. When an animal brushes against the hairs, the door opens and the animal is sucked in and digested

Combining observations in growing plants, 3D imaging and genetic analysis, the team will gain new insights into rules of growth at cellular and tissue levels and how they are controlled genetically. The scientists will also investigate whether there are common principles between different carnivorous plants and also with other plants and even animals.