Dig through archive answers century-old questions on flower colour and patterning

Questions on flower colour posed more than a century ago have been resolved by new research.

A collaboration between the John Innes Centre and Plant & Food Research, Palmerston, New Zealand, used historical archives and modern molecular analysis to shed new light on the work of Erwin Baur, an early advocate for the new science of genetics.

German scientist Baur was fascinated by garden snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) and established it as a model genetic system to understand how genes contribute to flower colours and patterning.

During the early 1900s, seed catalogues such as those from the Haage & Schmidt Nursery (Erfurt, Germany) had extensive collections of Antirrhinum with diverse colours and patterns (more than 100 varieties), including magenta, yellow, bi-colours, striped and bullseye patterns (called “Picturatum”). These patterns arise from differences in concentrations and patterning of magenta (anthocyanin) and yellow (aurone) pigments.

Floral pigmentation is an important cue to attract pollinators for reproduction, and usually involves patterning and contrasting colours. Diffuse, self-colouration is important for long-range target recognition, while high-contrast patterns, called ‘nectar-guides,’ act as landing lights that direct pollinators towards the nectar or pollen reward.

In 1902, just after the rediscovery of Mendel’s work on heredity in pea, Baur started to source varieties of Antirrhinum from the nursery of Haage & Schmidt in Erfurt, Germany (Baur, 1910).

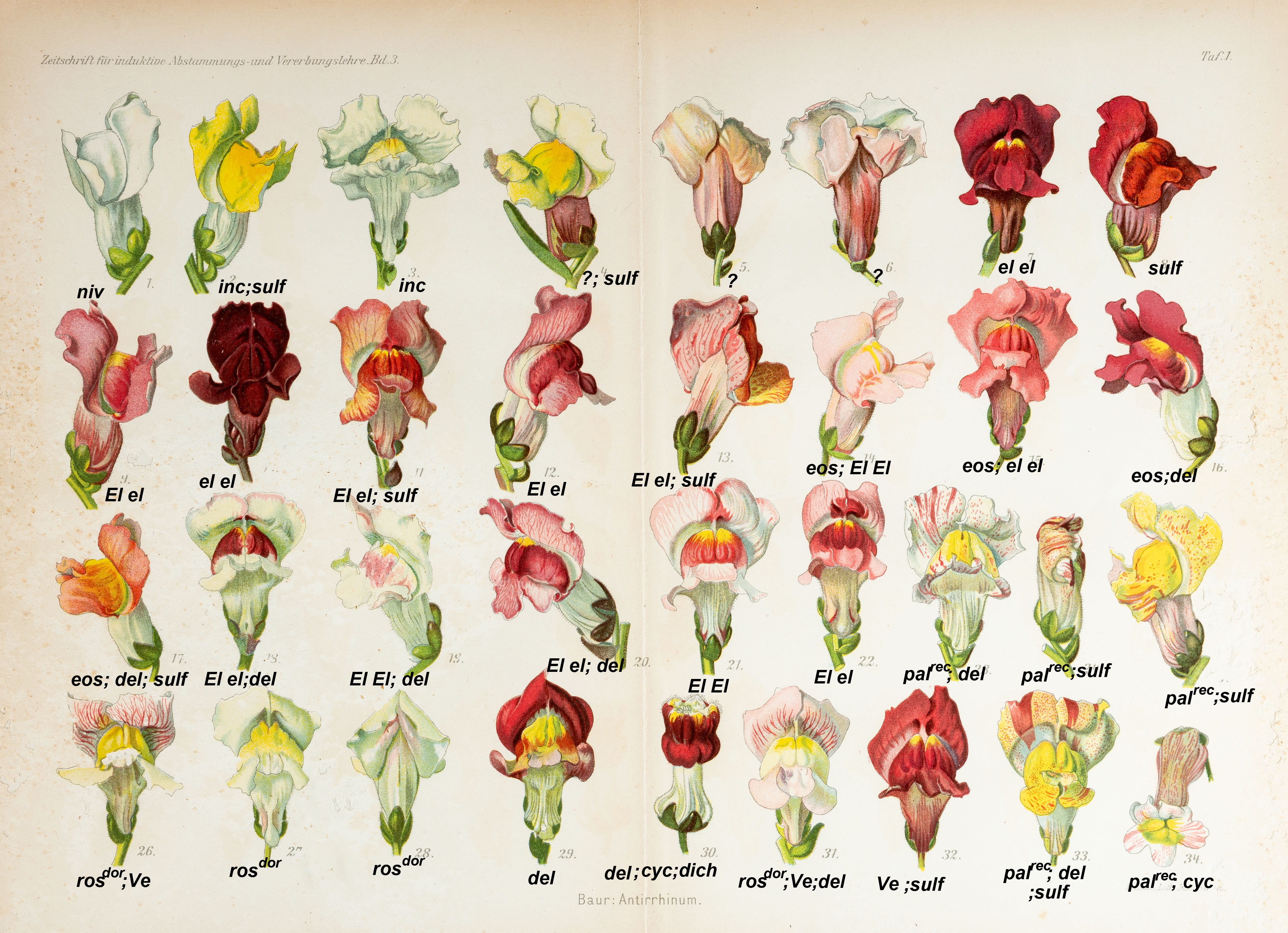

In a paper recently published in New Phytologist, researchers in the John Innes Centre-New Zealand collaboration traced the origins of the original Eluta/Picturatum variants described by Baur back to the early 1900s and identified the gene responsible for the Picturatum phenotype. The gene, now known as Eluta, inhibits and restricts magenta anthocyanin production in outer parts of the corolla of the flowers to generate a “bulls eye” pattern which is believed to attract bee pollinators.

Based on this work and research on flower colour in Antirrhinum dating back continuously to the foundation of the John Innes Institute, researchers can now assign mutations and mutant combinations to almost all the phenotypes illustrated by Baur in his first publication on variation in Antirrhinum.

These findings show that the origin of the Eluta/Picturatum variant was an introgression between a wild, yellow-flowered species, Antirrhinum latifolium and cultivated snapdragon (A. majus). Such a hybrid was probably selected by nurserymen because of its strong, high contrast bullseye patterning that would appeal to home gardeners.

This research linked foundational genetic experiments undertaken 120 years ago with modern molecular analyses and provided evidence that addressed some of the earliest questions in genetics, such as the identity or indeed the existence of a “wild type,” the species as it occurs in nature.

One of the authors Professor Cathie Martin FRS, a group leader at the John Innes Centre, said: “It was possible only because of access to the invaluable collection of books and manuscripts available through the Archives and History of Genetics collections at the John Innes Centre, the enthusiastic support of the archivist Sarah Wilmot and librarian Chris Groom and the public release of the seed catalogues of Haage and Schmidt Nurseries extending back to the 19th century.”

Deduced genotypes of Antirrhinums illustrated in Baur (1910).

Image: Phil Robinson/Cathie Martin