How do plants defend themselves?

Dr Phil Carella is the latest scientist to start his lab and join us here at the John Innes Centre.

Before he unpacked his bags, we sat down with him to learn more about who he is, what his group will be working on and how he became our latest Group Leader;

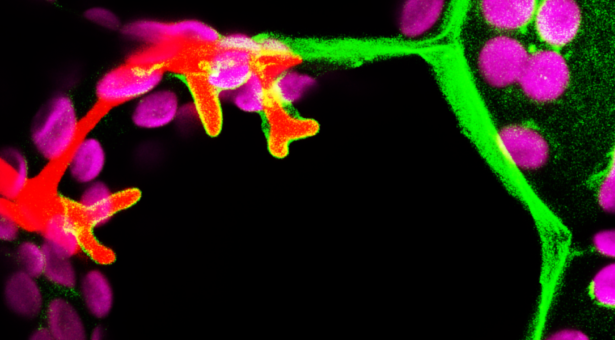

“Plants interact with a very broad range of microbial life forms in their natural environment.

In most cases this isn’t an issue, but sometimes these interactions can have profound impacts on plant health – either positive or negative.

To protect against infection from harmful pathogens, plants have evolved very sophisticated defences that can be remarkably fine-tuned given the degree to which they overlap.

When we think about plant diseases, we tend to focus on specialised interactions leading to susceptibility or resistance – but I think the fact that most plants resist most microbes is something really important from a macroevolutionary perspective – how do they accomplish this?

The overarching theme of my research is to explore and understand the evolution of plant defence.

I’m particularly interested in understanding how the critically-important plant defence pathways of our crops were first established when plants colonised land, and how these have evolved across distantly-related plants.

What components of plant defences have been maintained over this >400 million year time span and what new innovations are waiting to be discovered across the diversity of plant life that we have yet to test in the lab.

Answering questions like these is an incredible high which only grows because each answer we find leads to even more interesting questions.

When I was a little kid I wanted to be zoologist. I was only interested in the weirdest animals though – like egg-laying mammals, which might explain my fascination with weird plants like Marchantia…

My undergraduate studies were focused on microbiology and biotechnology, and I imagined myself working in a clinical setting (I didn’t know any better), but I was always interested in plants.

Once I was exposed to plant-microbe interactions research that was it – I did an undergraduate research thesis that led to my PhD studies, postdoc, and now I’m lucky enough to be at the John Innes Centre.

Everyone knows about the world-class research, excellent technological platforms and the prominent research groups at the John Innes Centre, but I’ve also met a number of really talented students and postdocs (both within the institute and across the Norwich Research Park) and I think is a really good measure of success.

It seems like a really stimulating environment and I consider myself extremely fortunate to become part of that”.