Else Schulz; our mystery woman

Recently, a collection of sketchbooks came to light in the John Innes Centre archives. Normally, when a selection of books come to the collection, the archivists at least know who gave the books, where the books came from, when the books came and why they ended up in the collection.

However, our Historical Collections team knew none of that. So, Madeline Ridout was given the task of deciphering this mystery, with nothing to work with except her name: Else Schulz.

Madeline picks up the story;

I felt the best place to begin unravelling the mystery of Else Schulz would be within her sketchbooks, I began to explore them, looking for the tiny details that could unravel who our mystery woman was.

The first book I looked at was quite interesting. The text on the inside of the cover (which was in German) gave me a little insight into what Else Schulz was like, without even looking at her pictures. The text stated: “Meinen lieben Onkel Rickard gewidniel” which means “dedicated to my dear Uncle Rickard”. Of course, I had no idea who this Uncle Rickard was, but it showed that Else Schulz cared about her family, enough to dedicate a book to an uncle.

German translation was an ongoing problem as the majority of her works had labels written in German, made harder by Else’s awful handwriting. It was only in her later works, once she’d lived in England for a while, where she began to write the labels in English. Her handwriting had not improved.

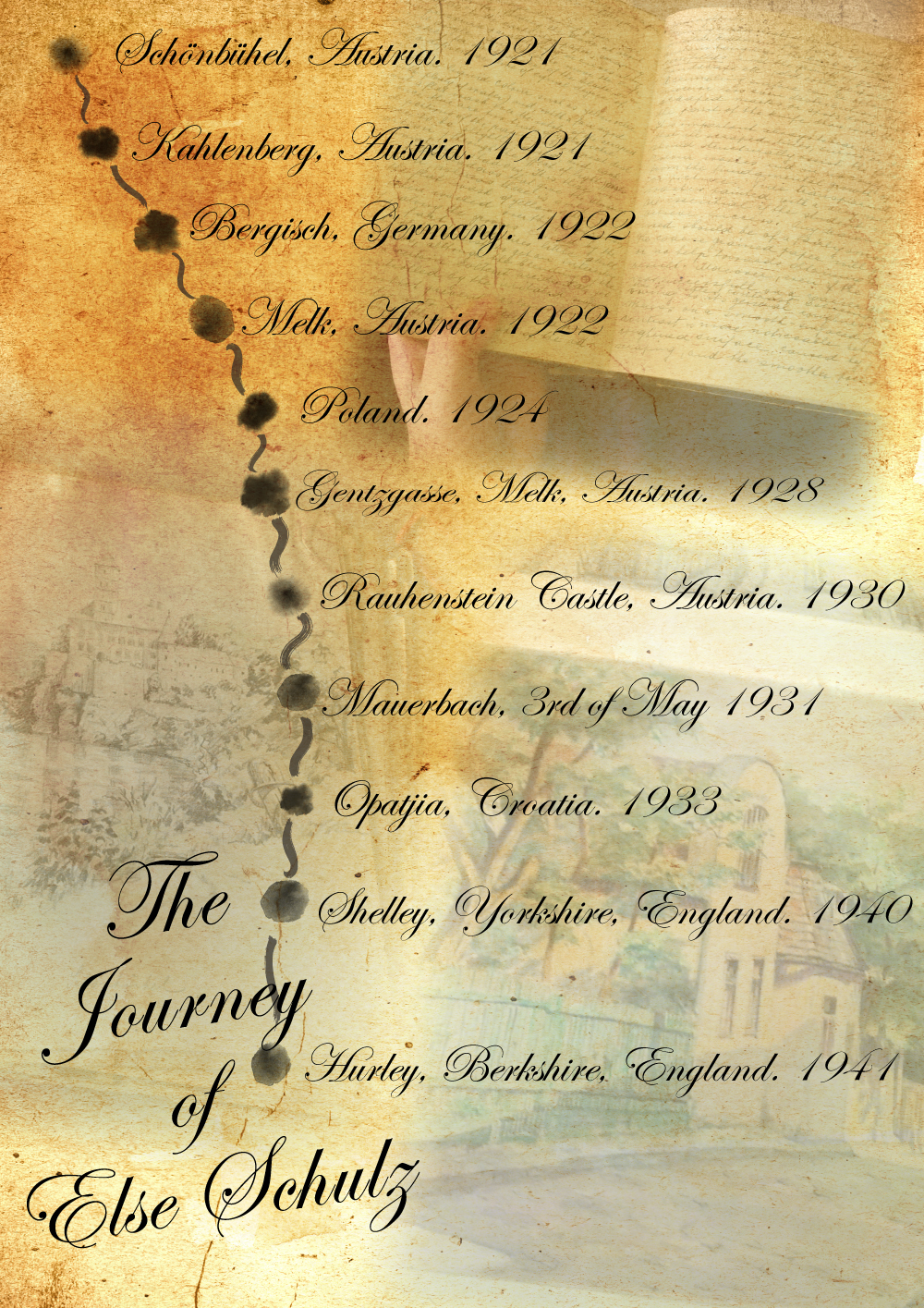

Even though her handwriting was bad, I was still able to decipher some place names. In the first book, Schulz had labelled a place as ‘Voloska’, so I did some digging and found a region of Croatia called Voloska.

Putting my detective skills to work, I began looking for a statue of a woman (which Schulz had drawn) in that region and was delighted to find there was indeed a statue of a woman in the region, in a place called Opatjia. However, something wasn’t quite right; the statue in Opatjia didn’t quite match the statue that Schulz had drawn. My suspicion was correct, as the statue of ‘a girl with a seagull’ had been erected in 1956, when the date that Schulz would have drawn the statue was in 1933. After an extra bit of digging, I found that ‘a girl with a seagull’ was a replacement statue for a previous one that had stood in its place, which was demolished during a storm. This statue was called the ‘Madonna del Mare’ and when I typed it into my handy search engine, I found a photograph with an uncanny resemblance to the statue that Schulz had drawn. Result! I had found that Schulz had been in Opatjia at some point during 1933.

But just because I had found out something new, did not mean I could then slack off… I still had many more books to get through before my time with the archives was over. So, feeling very pleased with myself, I pushed on to the next book.

The next book (affectionately known as ‘Book B’), was just as difficult as the previous book to find clues in. There were many times when I could have known her location but it was too difficult to read. There were some things I did find though. For example, I found out that Schulz had visited a place known for its castle ruins, a place called Schönbühel, in Austria.

Else also visited a town called ‘Melk’, which is west of Vienna, several times according to her sketchbooks. Generally, Schulz would only draw/paint landscapes or flowers, but near the end of ‘Book B’ she suddenly changes to anatomy drawings. It would be nice to know why she changed her main drawing theme suddenly, perhaps she started taking lessons? But who knows?

Moving on to Book C, there were very few clues into Schulz’s life, however the things I uncovered were pretty important. The first thing I found was a cheque receipt from ‘E & L Schulz’, which was for £9 (which was worth about £260 back in the 1930s). This raised some questions as to why Schulz had to pay someone that much, and why was it stuck haphazardly in a book with a drawing on the back. Unfortunately, these were more questions I was unable to answer in my time working at the archives.

There were also some locations which I found, both of which being in England. Here, drawings showed that she had been in Shelley, Yorkshire on October 14th 1941 and that she’d been in Hurley, Berkshire about a month or two later. The fact that she was registered in the registry office as an ‘alien’ displaced by war, and that Schulz is a Jewish surname, made me think that perhaps she was a Jew living in Austria (most of her recorded locations were in Austria, so I assumed that was where she lived), who needed to escape from Hitler’s clutches. After the war, Schulz returned to Austria and began to write her labels in English (which were a lot easier to read).

There was also a newspaper article stuck in Book C, about a ship called the ‘Discovery’. I was very confused as to how and why the newspaper article was there, as it was written in German, but about a boat in London. It just didn’t add up.

The other two books I was able to review in my time with the archive did not produce very much information at all as in indecipherable place names would not have dates next to them, which made them pretty useless. I did find three places though: Rauhenstein, Kahlenberg and Mauerbach, all of which are in Austria.

Overall, while I couldn’t come to any firm conclusions, I was able to make some progress with the information on Else Schulz and I developed two hypotheses as to why her sketchbooks ended up in the archive at the John Innes Centre.

Hypothesis one

Someone bought the collection of sketchbooks from Else Schulz because she was short of money, which would explain why many photographs were ripped out and the poor condition of the books.

The people who bought the books noticed that there were a few sketches with detailed botanical illustrations, so they came to the John Innes Centre asking if they were interested in the books. The John Innes Centre said yes, but ended up with the whole collection instead of just the ones with botanical illustrations.

Hypothesis two

Someone mixed up Else Schulz with Else Schultz, who was an earlier botanical artist. This theory is quite possible because the two women have very similar names and Schulz would draw botanical illustrations too.

At the end of my investigations, we can’t really know for sure, but if anyone has any further information on it, we would love to hear it.

The little things we may be able to find can’t really tell us about Else Schulz as a person, as the sketchbooks of a ghost are not a lot to go by. But I suppose the mystery that shrouds Else Schulz is what made this case so appealing to me; I was exploring uncharted waters and I was able to get the same sort of feeling as the people who explored and recorded the world for the first time, which is a sensation of excitement of all the possibilities to come.