Are we entering the endgame in the quest for a polio-free world?

The John Innes Centre is part of a global research collaboration taking crucial steps towards ridding the world of polio. The World Health Organisation-funded partnership has drawn together research institutes from the UK and USA to develop next-generation polio vaccines based on virus-like particle (VLP) technology, making them safer and more temperature-stable.

Professor George Lomonossoff, group leader at the John Innes Centre, said: “It is exciting that you can use the science we have developed to solve a real-world problem and, in this case, eventually result in polio eradication. It’s a wonderful example of collaboration which has taken us all the way from concept to the manufacturing stage.”

Poliovirus, the causative agent of poliomyelitis, has been a historic scourge causing crippling disease in humans, especially children. Most people who get polio show no symptoms; around 20% suffer mild flu-like symptoms and recover in about 10 days. One in 200 (0.5%) will develop poliomyelitis or paralytic polio, a crippling condition which can also cause permanent lung damage and lead to death.

Polio, if unchecked by vaccination, will continually cycle through populations, often transmitted via infected bathing water including large bodies of water such as swimming pools and rivers. For this reason, it used to be known as the summer plague in the UK.

Professor George Lomonossoff, group leader at the John Innes Centre, near the river Yare in Norwich, historically one of the epicentres of polio transmission in Norwich

Mass vaccination campaigns in the mid-20th century dramatically reduced prevalence of the disease. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative, launched in 1988, led to further vaccination campaigns, which reduced wild polio by over 99%. The wild virus is now endemic only in isolated pockets of Afghanistan and Pakistan. In recent years outbreaks have tended to develop in disaster-struck or war zones, such as in Syria in 2012, and more recently in Gaza. The increase in the number of polio cases when vaccination programmes are disrupted highlights the need for continuing vigilance.

To overcome the biosafety concerns associated with current poliovirus vaccines, there is a pressing need for risk-free alternatives that no longer rely on infectious virus cultivation.

Technology based around VLPs offers one such hope of risk-free vaccines that are thermally stable. In low-income countries and areas where war and natural disasters mean refrigeration is limited, these new vaccines could be an effective alternative.

VLPs against hepatitis B and human papillomavirus are widely used and have set a precedent for the efficacy of this technology. Now, in a potentially major step towards eradication, polio VLPs have been developed by a World Health Organisation (WHO) funded consortium led by the University of Leeds, together with the University of Oxford, the John Innes Centre, The Pirbright Institute, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), University of Florida, and the University of Reading.

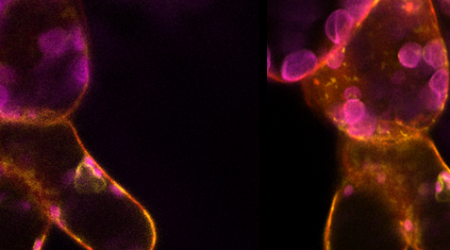

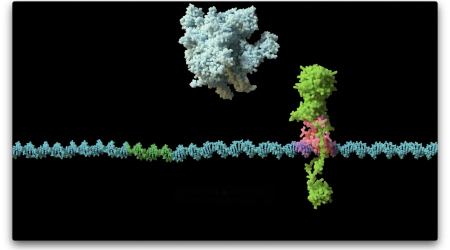

Model of plant-made polio VLP, based on structural data Credit: The University of Oxford, part of the WHO-funded poliovirus consortium

VLPs developed by the consortium are an authentic mimic of poliovirus, with all the features in the protein coat needed to train the immune system, but without the viral genome that allows the virus to replicate. One of the difficulties for researchers was that, in the absence of the infectious RNA genome, the protein shell of the VLP was unstable, which meant it could not elicit a protective immune response.

A breakthrough came when the consortium developed a method of obtaining stabilised particles that kept their shape without infectious material. Using evolutionary-based approaches, they identified mutations that allowed the maintenance of structure at higher temperatures and used this to design stabilised VLPs.

Professor Lomonossoff remarked: “Collectively, we have established that these poliovirus stabilised VLPs are viable as next-generation vaccine candidates for the post eradication era. We have shown that you can go from an idea of a stabilised shell and show that these stabilised shells work well in a variety of systems.”

Dr. Martin Eisenhawer, the WHO focal point for the development of Polio VLPs and the VLP consortium, said: “This research shows that a critical new polio vaccine solution is on the horizon. It would be a critical new tool to not only achieve but sustain global polio eradication in an equitable way – and ensure that no child anywhere will ever again be paralysed by any poliovirus. It is about ensuring that once polio is eradicated, it will stay eradicated.”

Complete eradication is achievable because polio only affects humans. Viruses such as influenza also affect animals, which makes complete eradication impossible. Eradication of polio is an achievable aim, and like another ancient scourge, smallpox, the summer plague may one day pass into history.

Why are next generation polio vaccines needed?

Vaccines produced in the 20th century were instrumental in halting polio epidemics. However, despite their success, these vaccines have limitations that obstruct the path to full eradication of the disease.

The Salk inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) developed in the 1950s is based on the inactivated poliovirus so requires the production of large quantities of the virus before inactivation. This poses risks of accidental release. Furthermore, IPV vaccinated individuals, whilst protected themselves, can still spread polio. This is because IPV provides only limited mucosal (gut) immunity (needed to interrupt person-to-person spread of the virus).

When a person protected with this vaccine is infected with wild polio virus it can still multiply inside the intestines and be shed in faeces – potentially continuing the cycle of infection.

WHO Regional Director, Dr Hanan Balkhy (left) administering polio drops to a child during a visit to Afghanistan, with Dr Hamid Jaafari, Director of Polio Eradication Credit: WHO/Zakarya Safari

Current IPV must be produced under extremely strict biosecurity conditions, to minimise the risk of containment failure of the infectious seed strain before it is inactivated, and this contributes significantly to the vaccine’s cost.

The Sabin oral polio vaccine (OPV), launched in the early 1960s, uses a weakened or attenuated form of the live virus to stimulate the immune system. This vaccine is needed to interrupt transmission of the virus, thanks to its unique ability to induce mucosal immunity.

However, because it consists of weakened strains of the virus, its use can sometimes be associated with outbreaks of circulating vaccine derived poliovirus, and therefore its use will be stopped after global eradication of remaining wild poliovirus strains. At that time, IPV or VLPs will be the only vaccines that will be able to maintain population immunity.

Turning polio vaccines into commercial reality

Having established proof of concept, the current question facing the WHO-backed consortium concerns which biotechnical system may be best to produce polio VLPs so that they can be scaled up and used in vaccines. In a study published in Nature Communications, the researchers compared four different production systems to produce VLP vaccines: plants, yeast, insect and mammalian cells. Experiments using animal models compared antigenicity, thermostability and immunogenicity of these polio VLPs against the current IPV.

Some of the VLPs demonstrated equivalent or superior immune response and enhanced stability at elevated temperatures than the current IPV vaccine. Previously the consortium used plants as an expression system to produce VLPs in an influential 2017 study, and plants remain a highly efficient and useful way of expressing pharmaceutical particles rapidly at low cost.

However, commercialisation of these polio-vaccine VLPs is likely to be carried forward in yeast or insect cell expression systems. This is because the drug production industry currently favours these approaches as they are already used for VLP production, are low cost, and available in low- and middle-income countries.