Bacteria branch out

Streptomyces produce the majority of clinically useful antibiotics, yet we don’t fully understand how they grow.

PhD student Antje Hempel has contributed to our understanding of this by working out how and why the bacterial filaments produce branches.

Professor Mark Buttner, Antje’s PhD project supervisor said: “Unravelling this mechanism has been all the more remarkable as Antje became a mother during the course of her PhD, and it is testament to her ability that she still completed her studies on time.”

Streptomyces bacteria typically live in soil and survive by decomposing plant matter.

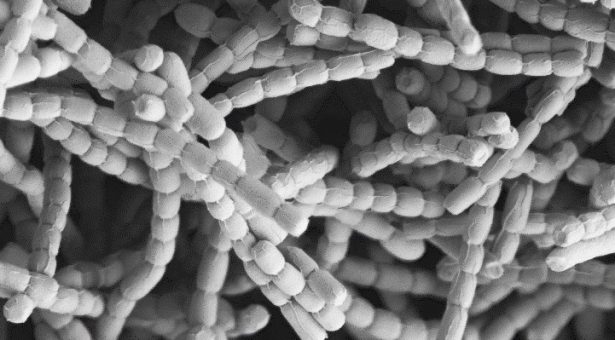

They do this by growing a large branched network of filaments, called a mycelium. They produce a huge array of different enzymes to feed their metabolism from different sources, as well as producing protective compounds. These compounds have been well studied because they are useful to use as antibiotics and other medicines, but the actual growth and development of the bacteria that produce them has been more of a mystery.

Streptomyces are different from other bacteria. Their branched filamentous growth resembles that of fungi more than that of other bacterial genera. Also, their cells grow from the tips, rather than the more orthodox way typical bacteria elongate in the middle of cells, and very few research groups have looked at this type of polar growth.

In 2005 Antje Hempel joined one of these groups, Klas Flärdh’s group in Lund, Sweden, as part of an ERASMUS exchange from Heidelberg University where she was studying biology. Klas Flärdh has had a long-standing collaboration with Mark Buttner, and in 2008 Antje started a PhD at the John Innes Centre under the joint supervision of Mark and Klas.

Klas Flärdh had previously shown that polar growth is dependent on a protein called DivIVA, which accumulates at the growing tips and directs cell wall synthesis.

In a paper published in PLoS Computational Biology, Antje and colleagues at the John Innes Centre and Lund showed how branch sites are selected and branching is initiated. DivIVA accumulates into foci, from which branching initiates.

Antje showed that these DivIVA foci don’t form spontaneously, but splinter off from existing foci and get left behind on the lateral membrane as the tip grows away.

Antje worked with John Innes Centre computational biologists David Richards and Martin Howard to produce mathematical models of how this system works.

Foci can split and produce a daughter focus, typically about 10% the size of the original. The daughter focus grows in size until it reaches a critical mass, when it can then trigger a new branch. The tip to branch distance is determined by how long it takes the daughter focus to reach critical mass, and the number of branches depends on how often foci split.

Antje’s painstaking measurements of these factors experimentally confirmed the predictions of the model.

The model also predicted rare events where the tip focus splits into two approximately equal-sized daughter foci that are both large enough to trigger immediate branching. Exactly such splitting events were observed experimentally, giving rise to branching at the growing tip, verifying this prediction from the model.

The model explains how new braches arise, but it also provokes questions about whether Streptomyces can manipulate its branching, and why.

Research being published in PNAS Plus has now shown how the process of branching is regulated. Antje showed that DivIVA is controlled by phosphorylation and identified the specific kinase responsible.

During normal growth only low levels of DivIVA phosphorylation are seen. But when tip growth is blocked with cell wall synthesis inhibitors, mimicking when the growing tip hits an obstacle in the soil, this triggers phosphorylation of DivIVA, which changes the branching pattern of the organism.

“What this suggests is that when Streptomyces hit an obstacle, it rearranges its branching pattern to grow in different directions,” said Mark Buttner. “Antje’s work with me and Klas Flärdh has shown how and why this happens, giving us a much better appreciation of how these important bacteria grow through their environment.”

Antje’s PhD research was selected by her peers at the JIC’s Annual Student Science Meeting to be presented by Antje at the full John Innes Centre Annual Science Meeting in October. Before that, in August 2012, she will take up a Postdoc position with Urs Jenal at the Biozentrum in Basel, Switzerland.

“Unravelling this mechanism has been all the more remarkable as Antje became a mother during the course of her PhD, and it is testament to her ability that she still completed her studies on time. I wish her all the best in her future career,” said Mark Buttner.